With a career spanning over five decades, Dave Holland is without a doubt one of the jazz world’s most acclaimed bassists and composers. Just prior to the lockdown, Darrell Craig Harris sat down with Dave for an extensive interview. Dave speaks about his early life in the UK, his initiation into the Miles Davis Band and of course his latest release with Kenny Barron and Jonathan Blake.

Dave Holland is the recipient of multiple Grammy® awards and in 2017 received the title of NEA Jazz Master. On 6 March, Dave released a new trio album titled “Without Deception” together with Kenny Barron and Jonathan Blake on his own label, Dare2 Records. To support this release the trio had planned an extensive tour throughout the USA and Europe. However, the current Covid-19 pandemic put paid to this. This Interview was conducted just prior to the lockdown.

______________________________

Editors Note: The following Interview is an abridged version of Darrell’s interview with Dave Holland that appears in the Spring 2020 edition of the Jazz In Europe Magazine. Prior to Darrell’s question about London in the mid-60’s Dave spoke in detail about his early ears and how he came developed a love for the Bass. Later in the interview Dave speaks in detail about some of his current projects, his label and a great deal more. You can read the full un-abridged interview in the Spring 2020 magazine.

______________________________

DCH: The mid-60’s must have been a really exciting time to be in London. There had to be so much happening there at the time. What was the experience like for you as a young musician and a young man?

DH: It was really exciting for me. There was so much happening in my life and just every day was a learning experience. I was on the path of being a musician and I couldn’t believe it. It was my dream coming true at the time really. When I first moved to London, I spent about nine months playing at a Greek restaurant and I was studying bass with a very fine classical bassist, James Edward Marrot. He was the principal bassist with the London Philharmonic Orchestra at the time and was teaching at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama, a very good school.

In those days they only had classical courses and after studying with him, one lesson a week for about nine months, he suggested that I audition for the school. So, in ‘65 I started a three year course there.

DCH: What was the London jazz scene like at that point? From what I’ve heard it was pretty vibrant.

DH: Well yes, the music scene was very vibrant. All kinds of crossover things were going on between blues and jazz. For instance, there was a group called Indo Jazz Fusions led by West Indian musician Joe Harriet. It was a very wide-open kind of time and being a bass player I enjoyed all the different things I had the opportunity to do. There was a very solid traditional group of older musicians in London that I got to play with, and the early New Orleans style was very popular in pubs. Some of the first gigs I did actually were with these kind of bands, playing arrangements by King Oliver and Armstrong.

And then I met up with musicians my own age and we were listening to all the new music coming out of America, Coltrane, Ornette Coleman, Miles and all that! I was just staying up all night listening to records, and playing as well, just trying to learn as much as I could from it. I’d also meet musicians who were coming to London from the States. Through my gig at Ronnie Scott’s Club, where I started working in 1966, I started playing with some of the visiting American jazz musicians. That wasn’t a full-time thing. The club would hire rhythm sections to play with different visiting musicians and I got to do several things there.

DHC: It seems that Ronnie Scott’s is still to this day probably the top club in London to play, so that must have been an exciting time back then to see and interact with all the stellar players coming through! I can imagine it was really exciting as a young jazz musician.

DH: It was, and the thing is in those days, musicians did three or four weeks as a residency. It wasn’t just two nights like it is now. They would come in and I was in the support band, so I got to play opposite the Bill Evans Trio with Eddie Gomez and Jack DeJohnette. I was in the support group opposite them and we’d do alternate sets.

DCH: Being around those players for that length of time, you actually had the opportunity to really get to know them one on one.

DH: Exactly. That’s how I got the meet Jack DeJohnette and become friends with him, you know, long-time friendship there.

I was also gigging, doing studio work, short half-hour jazz programs on the radio—which believe it or not, they used to have. It was also normal studio work, film music and all kinds of different gigs. I went on tour with Roy Orbison, did all kinds of music but, increasingly more and more jazz at that time.

DCH: So I have to ask this. Can you tell me about meeting Miles, and how gigging with him happened for you?

DH: Well, I didn’t actually meet Miles until I turned up for the gig. I’ve mentioned the story many times, but I was working at the Ronnie Scott’s Club opposite the Bill Evans Trio. Jack and Eddie were there, and I was playing in the backing trio for a fine singer that I occasionally played there with, when Miles came into the club to see Bill, I guess. Bill had of course worked with Miles, but Miles wasn’t working in London at the time. He just dropped in for a visit and stayed all night.

Anyway, Philly Joe, who had been in London for about a year, a year and a half, was also there, and he brought me a message as I was going on for my final set. He said Miles had asked him to come over and tell me that he wanted me to join his band. As you can imagine I was stunned. I didn’t expect it. I wasn’t even thinking about him (Miles) listening to what we were doing! I’d just gone on with doing the gig, which is probably a good thing. If I had tried to show off, I’d probably have never gotten the gig.

DCH: I interviewed Christian McBride sometime back and he was talking about the time when Ray Brown came and saw him and how nervous he was. He said his hands were shaking and he was sweating and (laughs) you almost don’t want to know those guys are sitting there watching you.

DH: Well honestly, I didn’t think he was listening, so I wasn’t nervous. I was just playing the gig and doing the best I could. It was a fairly traditional book of music, well arranged, and some good players I was playing with, and so I was playing for the band and for the music.

DCH: How did you prep yourself to do the Miles gig? You said that you didn’t actually meet Miles until the day of your first gig with him. Is that correct? Did they send you a song list? Or how was that handled?

DH: No, no, nothing. I just got a call after that evening when I got the message from Philly Joe. Philly, at the time, said Miles wants to speak with me after the set, but of course when I finished the set, Miles had left and he’d gone back to the hotel. Philly Joe was still there and he said, “Call him at the hotel tomorrow.” He gave me the name of his hotel and about 10 or 11 o’clock the next morning I called the hotel and the receptionist told me that Miles had checked out and had gone back to New York. So I was just waiting. I called Philly Joe later in the day and asked, “What do you think is going on?” He said, “Just sit tight,” and I said, “Is he serious?” he replied, “If Miles tells you he wants you to join his band, you can take that as written. He wouldn’t be bull shitting you.” I said, “OK, I’ll just sit tight.” So a couple of weeks went by, actually three weeks, and by then everybody I knew in London was calling me saying, “What’s going on?” (Laughs)

I was just waiting, and then I started a gig with Joe Henderson. I was playing in the rhythm section accompanying him at Ronnie’s. It was at the start of another two or three week residency. We finished that first night and after I came back to my apartment, the phone rang at about 3 in the morning and it was Miles’ manager. His name was Jack Whittemore, a very nice man. Jack basically said, “Miles wants you to come play with him.” This is a Tuesday, right! He said, “The gig starts on Friday. The place is in New York, can you make it?” I said, “Yeah! OK, I’m ready.”

I had some time to think about it and I knew that’s what I’m gonna do. I wanted to go to New York anyway. This was in the summer of ’68 and I was finishing up my studies at the Guildhall and I’d planned to take a trip to New York anyway. I had a number of people I knew there and had already mentioned I was going to visit them. They had all said, “Come to New York. We’ll try to connect you up with some things.” That would have been September or October that I was planning to go, but here I was on stage with Miles in August.

DCH: What a great way to come onto the American jazz scene, right? (laughs)

DH: Oh, it was amazing, and you know, I have to say I wasn’t so nervous that I couldn’t play, but there was definitely a little bit of tingle in my stomach on that first night. I mean, I wanted to do well. I had so much respect for the band. I had listened to the band on record, listened to Ron and how he played and I admired that so much. I knew Tony was a little scary, he’s such an amazing drummer, you know, rhythmically developed, and Herbie! It was just an amazing night to get up on stage.

So, I hadn’t met Miles or anything, and I got to the club, set my bass up on stage, nobody else was there, I got there kinda early. And then one by one, everybody arrived, but nobody took much notice of me. I do have to say the night before I got a message saying that when arriving in New York I should go see Herbie at his apartment. So I went that evening and Herbie showed me a few of the songs.

They were mostly some of Wayne Shorter’s tunes that hadn’t got around to being in the repertoire enough for me to know the real version of, how the real chords were. So Herbie helped me out with those, and that was it. I had spent maybe an hour and a half, two hours with him.

As I said earlier, the next night I turned up at the club and once everybody was there and on stage, Miles just started the first tune right from his trumpet. There were no suggestions about what the set would be or anything like that really.

DCH: What club was that?

DH: That was the Count Basie club in Harlem.

DCH: Awesome. So you obviously went on to record with Miles, and Bitches Brew, soon celebrating its 50th Anniversary, is of course a legendary album. Can you tell me a little bit about that experience and how that was for you?

DH: Well I can, but the thing is that we were going into the studio pretty much every time we’d come back to New York. So there would be a day or two that we’d go to Columbia Studios and record. And the Bitches Brew session was just another one of those sessions. It wasn’t like, “Okay, now we’re going to go in and record this album.” As you can see from the recorded material, tracks were done on different days and different times. Afterwards the albums were compiled from those sessions. That particular session was extraordinary because it was a large group, and you know, with an amazing group of musicians.

DCH: It was really a who’s who of amazing jazz musicians of the time!

DH: Yes, we had three or four keyboards. I mean Larry Young I think was there, Herbie, Joe Zawinul and Chick Corea. We had a couple of drummers maybe. You know it’s hard for me to remember everybody that was there! We had so many players.

DCH: Well, It’s a very long list.

DH: Yeah, and you know, none of us really knew what we were doing in a sense. It wasn’t like there was a tune where we play the head, play some solos and then take it out. That wasn’t how the music was going in those days. With Miles there was a very free feeling to the whole process. There was definitely material, but it was a minimalist kind of thing—a melody here, bass line there and we would just start things going, well, Miles would just get things going and then as we were recording, he might point to Wayne or just look at Wayne and he would start soloing. It had this very loose and free kind of thing and, of course, that comes through in the music. It was sort of searching as well. Somehow the keyboard players were all trying to figure out how to make it work with multiple keyboards. Miles created this setting where it all came together. It was fantastic.

DCH: That was such a legendary group of musicians. Everybody for sure had something to bring to the table.

DH: (chuckles) Yeah I think so.

DCH: What’s fun and interesting is that on some of the recordings you can actually hear him directing the band / players while you guys are actually recording?

DH: Well on the sessions that would be how it would go. Occasionally we’d rehearse at his house just to go over some material. Sometimes we wouldn’t even use it the next day. We’d do something else. He’d be just trying something. Then we’d get in the studio and sometimes he’s just had some idea or he’d maybe talk to whoever the drummer was to try something. He might give him some indication of the kind of thing he had in mind. Sometimes he might refer, just kind of bleak references, to another recording or something on a tune that he heard somewhere.

DCH: It’s nice as a young musician to be given that kind of freedom, right?

DH: Oh, it was fantastic. I never felt Miles was kind of imposing restrictive parameters on the music in that sense. Certainly on the live things, we were taking a lot of liberties with it.

DCH: And you were playing both upright and electric at different points with him?

DH: Yeah. After about a year of being in the band, in fact it was after Bitches Brew came out, I think I said to Miles that I felt like the bass guitar would work better in some pieces. After all we were using electric pianos quite a lot by then. I can’t remember exactly how it went. I do remember volunteering because I was still playing everything on acoustic even though there were these groove bass lines. My memory is that I said, “Look, you know, I could play bass guitar on some of these tunes.” Miles called up Fender, at the time they were associated with CBS, and got me a Fender bass.

DCH: At that point, he was really starting to venture into using a more electronic type of instrumentation. Was that fun for you to explore and try different feels etc.?

DH: Well we were trying all kinds of things. There were some electronic things being used, fairly primitive at that time compared to now, but it was giving some other textures to the music. It was great; it was super creative. That’s all I can tell you. And it’s the kind of experience that lasts with you for your lifetime. Creating with him and having that freedom!

DCH: You have recorded a number of different albums with Miles both in the studio and live, correct?

DH: Yes, that’s correct. There was Live at the Fillmore and Black Beauty, which is live at the Fillmore West. Then there are some compilations where there were some tracks with me and some tracks with Michael Henderson.

DCH: It’s amazing that all of your history with Miles starts with him walking into Ronnie Scott’s that night and seeing you, amazing how that works.

DH: That’s how life works, isn’t it? You know, things converge and then they go off in different directions and that’s how life is. You meet your future wife somewhere just because you got off the bus at the bus stop.

![]()

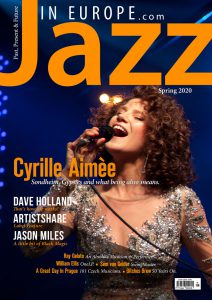

Jazz In Europe Magazine – Spring 2020 Edition

This article is an abridged version of the full interview that appears in the Spring 2020 edition of the Jazz In Europe print magazine.

Also included in this edition are interviews with Cyrille Aimee, Ray Gelato, Dave Holland, Jason Miles and Sem van Gelder. We take a look at Bitches Brew, 50 years on. Tony Ozuna presents us with a look at the Czech jazz scene from it’s origins behind the Iron Curtain to the present day. This editions photo feature spotlights British photographer William Ellis.

Also included in this edition are interviews with Cyrille Aimee, Ray Gelato, Dave Holland, Jason Miles and Sem van Gelder. We take a look at Bitches Brew, 50 years on. Tony Ozuna presents us with a look at the Czech jazz scene from it’s origins behind the Iron Curtain to the present day. This editions photo feature spotlights British photographer William Ellis.

You can purchase a copy of the magazine here.

Last modified: July 19, 2020