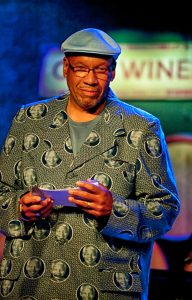

Willard Jenkins by Enid Farber

Willard Jenkins biography describes him as ‘consultant, arts administrator, artistic director, writer, journalist, broadcaster, educator and oral historian’. This doesn’t even touch the surface of the significant work Willard Jenkins has done and continues to do. He is a role model and inspiration to many people across the globe and I include myself as one of the many. It is not just his extensive knowledge of jazz history, or his experience as a writer or artistic director that is inspirational. It is the truth and energy within the depth of that knowledge that he exudes through all of his work. There is something undeniably majestic and magical about Willard Jenkins.

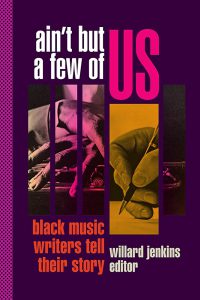

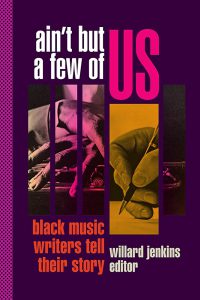

The importance of Willard’s new book Ain’t But A Few of Us: Black Writers Tell Their Story cannot be underestimated. A collection of journeys – lived experiences – from the voices of 49 truly inspirational black writers. It is groundbreaking for many reasons. Groundbreaking because never before has the lack of black jazz journalists been documented. Groundbreaking because never before has such an inspirational collection of writers been given a platform to share their experiences. Willard has given a long overdue platform to incredible voices.

There was much to explore with Willard and although an obvious starting point, especially considering these historic issues, I asked Willard what led him to create this book now at this particular moment.

WJ: This is a conversation that actually started with a series of interviews in 2010. Those interviews were published on my website, and they became a series which kind of snowballed. As I became acquainted with others and came into contact with others who I had not previously been in contact with, people that had been recommended by other participants, it evolved from there. After that point and I can’t really say exactly at what point, but it became clear that there may be a book here. In fact, I think it may be Eugene Holley, one of the contributors, who first dropped that dime on me… he planted the seed. I had a good relationship with the Duke University Press when I wrote Randy Weston’s book (African Rhythms: The Autobiography of Randy Weston) and so it was only natural to go to them and see if there was interest. They were interested in the whole idea and it then became a matter of taking the interviews that were originally published online adding some more, shaping them into book chapters and providing each one of the participants with a chapter so to speak, a forum for discussing their development and their careers and how they got to writing about music etc.

WJ: This is a conversation that actually started with a series of interviews in 2010. Those interviews were published on my website, and they became a series which kind of snowballed. As I became acquainted with others and came into contact with others who I had not previously been in contact with, people that had been recommended by other participants, it evolved from there. After that point and I can’t really say exactly at what point, but it became clear that there may be a book here. In fact, I think it may be Eugene Holley, one of the contributors, who first dropped that dime on me… he planted the seed. I had a good relationship with the Duke University Press when I wrote Randy Weston’s book (African Rhythms: The Autobiography of Randy Weston) and so it was only natural to go to them and see if there was interest. They were interested in the whole idea and it then became a matter of taking the interviews that were originally published online adding some more, shaping them into book chapters and providing each one of the participants with a chapter so to speak, a forum for discussing their development and their careers and how they got to writing about music etc.

This is not a book of aggrieved writers expressing their gripes. This is a group of writers, who have had varied experiences that has got them to the place they are at now with their writing. Experienced writers that talk about where they are now with their writing and how their experiences have colored their writing and how these experiences, at certain points along their pathway, may have touched upon elements of this and what I refer to, as many refer to, is the specious man made concept known as race; and whether there are situations that they bumped into along their path to writing about music that suggested some elements of race. In most cases, all of the contributors of this book had experiences that in some way shape or form were shaped by perceptions related to race so that basically, was the premise of the book.

The book is separated into chapters: The Authors, Magazine Editors and Publishers, Dispatch Contributors, Magazine Freelancers, Newspaper Writers and Columnists and The New Breed, allowing for a dynamic range of writers to share their journeys in a wide range of contexts. I asked Willard if this was intentional from the beginning or if this was something that evolved.

Willard Jenkins, A.B. Spellman, Steve Monroe, Gene Seymour and Don Palmer

WJ: That kind of arose organically. It’s not as though I went into an interview saying to myself well, this particular person is an author, or this particular person is representative of a certain sector of the writing. Those headings that you refer to, the authors, the black dispatch contributors, freelance writers etc those came organically as I made my own determinations of where I thought those particular writers best fit in terms of those groupings. For example, in the interviews, there were certain group of writers that contributed to this book who are authors, so let’s take for example Karen Chilton. The greatest degree of her music writing has come in the two books that she’s contributed. One on Gloria Lynne (I Wish You Love: A Memoir) and one on Hazel Scott (The Pioneering Journey of a Jazz Pianist, from Café Society to Hollywood to HUAC) so naturally she was going to be one of those who would be in the author column… so those headings arrived organically.

The content of the book, laid out in this way also includes a truly inspirational anthology at the end, which is a collection of articles from 1946 to 2016 including Leroi Jones’ ‘Jazz and the White Critic’ written for Downbeat in 1963 and John Murph’s ‘Rhapsody in Rainbow: Jazz and the Queer Aesthetic’ written in 2010. This book should be essential reading and included in curricula across the world, especially considering the complete lack of representation – and with increasingly more conversations about what little is there being removed through the devastating actions of certain US politicians. I asked Willard if the educational value of this book was a consideration during its development.

Janine Coveney, Bridget Arnwine, Jordannah Elizabeth and Willard Jenkins

WJ: Not necessarily and that wasn’t one of the driving factors behind completing and putting out this book. I do recognise, as you say, that there are elements of education particularly where it regards not only the inclusion of all of these contemporary writers, and I use the term contemporary guardedly because unfortunately in the interim some of the contributors have passed on to the ancestry. The anthology aspect of it which you mentioned is where we have a section of the book that is comprised of the contributions of certain black writers on music and a few of the anthology pieces actually came from contributors to the book, pieces that I thought were important in explaining who these writers are and what some of their motivations were. But it was also important, I felt, to represent the ancestors. Leroi Jones (Amiri Baraka) in his initial jazz writings wrote a very important piece called ‘Jazz and the White Critic’ and that is the first piece in the anthology because that piece and the citations that he makes in that piece, the questions that he asked in that piece, these are core questions and are the core premise of this whole book.

I also wanted to represent A.B. Spellman in the anthology. As well as being a contributor of one of the interview sections, consistently, when I would interview these writers and they would talk about some of their inspirations and how they came to write about the music, they would consistently cite Leroi Jones (Amiri Baraka) and A.B. Spellman as being two of their inspirations. It was also essential to have Barbara Gardner. There has only been one African American woman who has served once in an editorial position at a major jazz publication and that was Barbara Gardner. Barbara Gardner was an associate editor of Downbeat magazine in late 50s, early 60s so it was important to have her represented in the anthology. There’s also a man named Marc Crawford who wrote a beautiful piece about Bud Powell’s passing that is included in the anthology and Marc is also someone who was cited as an inspiration and someone I had known through the years as a fellow writer and so I was very happy to include him in the end as well.

Dr Tammy Kernodle

The wide range of writers in the book allows us crucial insights into their writing journeys and how they developed. In the opening roundtable discussion, Jordannah Elizabeth shares that ‘there is a disconnect between music publications, black life, and access.’ Dr Tammy Kernodle tells us about her days as a student and how she was told by her professor that ‘No American, no black and no woman has ever made any substantial contribution to music’. John Murph and others discuss the lack of role models ‘back in college I didn’t see music journalism as a viable career option because there weren’t that many role models at the magazines, particularly African Americans from my generation’. Despite these glaringly obvious obstacles, one of the many elements of the book, that stood out to me, was the truly graceful way, the writers discussed and explored these unacceptable barriers. The quality of the writing throughout the book is astounding.

WJ: It’s quite incredible because with that sense of grace they are able to tell their stories in a clear manner that is not overly colored by anger or by the frustration of their journeys. I consistently asked everyone the same questions and I think the combination of that and the fact that these are writers that all have a certain grace about them, about their sense of jazz music and their sense of the need to write about these artists.

A quote on the back of the book from Shana L Redmond says, ‘The variety of their paths to writing and the insights revealed by it demonstrate why Black writers’ voices and interventions are needed now as much as ever’. So for my last question, I asked Willard about possible interventions and what he hopes people would take away from the book.

Willard Jenkins speaking at Randy Weston’s Funeral. Randy’s piano is in the foreground. St. John’s The Divine, NYC 9-10-18, by Enid Farber

WJ: I hope they would take away the fact that we are the ultimate beneficiaries of a broader more diverse pool of reportage about this music and that ultimately the music benefits from a broader more diverse perspective of criticism and journalism. I would hope that people would take away that these perspectives need to be broadened. We need a more diverse sense of this music and I say that not only from an ethnicity or racial perspective but also from a gender perspective as I’m sure you will know, this book could have been ‘Ain’t But a Few of Us Women’. I am proud of the fact that we have a significant number of women contributors to this book.

Thank you Willard. Thank you for all you do and for this incredible book.

Ain’t But A Few Of Us is a book for anyone who wishes to understand the truth of the jazz landscape and for anyone who enjoys brilliant writing. On a personal note, this book inspired me to create a new mentoring scheme for Women in Jazz Media to increase the number of black jazz journalists. In partnership with Black Lives in Music the mentors include three writers from the book – John Murph, Jordannah Elisabeth and Willard himself. To anyone who has a publication, a site or any type of platform that covers jazz, I am excited to see how this book has impacted your work and I look forward to reading more ( the first, in too many cases) black voices on your platforms.

Purchase Ain’t But A Few Of Us: Black Music Writers Tell Their Story

Purchase Ain’t But A Few Of Us: Black Music Writers Tell Their Story

Edited by Willard Jenkins

Contributors: Eric Arnold, Bridget Arnwine, Angelika Beener, Playthell Benjamin, Herb Boyd, Dwight Brewster, Bill Brower, Tina Brower, Jo Ann Cheatham, Karen Chilton, Janine Coveney, Marc Crawford, Stanley Crouch, Anthony Dean-Harris, Jordannah Elizabeth, Lofton Emenari, Bill Francis, Barbara Gardner, Farah Jasmine Griffin, Jim Harrison, Eugene Holley, Haybert Houston, Robin James, Martin Johnson, LeRoi Jones, Robin D. G. Kelley, Tammy Kernodle, Steve Monroe, Rahsaan Clark Morris, John Murph, Herbie Nichols, Don Palmer, Bill Quinn, Guthrie P. Ramsey, Ron Scott, Gene Seymour, Archie Shepp, Wayne Shorter, A. B. Spellman, Rex Stewart, Greg Tate, Billy Taylor, Greg Thomas, Robin Washington, Ron Welburn, Hollie West, K. Leander Williams and Ron Wynn.

Last modified: April 14, 2023