Shaw took credit, for instance, for reviving composer Thomas Griselle’s charming 1929 orchestral piece, Nocturne. His recording of it is indeed beautiful, and it was the first big-band version, but the John Kirby Sextet had in fact recorded it a year earlier. He took credit for the few times his own band used a string section in a jazz context, but those successes were really the work of William Grant Still (Frenesi), Ray Conniff or Paul Jordan (Suite No. 8). Moreover, for someone who was apparently always searching for the best in music, he clearly recorded a lot of charts that would, a decade later, fall into the category of Middle-Of-the Road music or MOR, such as Dancing in the Dark, Moonglow, Temptation, Star Dust, Dancing on the Ceiling etc. His motto in the early 1940s seemed to be: When in doubt, throw in a string section, soup it up and make it sappy, it’ll sell. It was a very cynical approach for a man who prided himself on his intellectual capacities. But there are still some people, largely non-musicians, who are bamboozled by this into thinking his use of strings was a form of art, among them biographer Nolan:

And his orchestral conceptions, his periodic use of strings and classical horns, and the arrangements he commissioned from such talented men as William Grant Still and Eddie Sauter changed the nature of big-band jazz.

No, it didn’t—at least not until Kenton’s arrangers began using strings in a jazzier context in the early 1950s, and even then there were some duds.

Jazz clarinetist Artie Shaw leads his band during a scene from the movie Second Chorus in 1940. — Image by © Bettmann/CORBIS

Yet just as Shaw had taught himself to read music at age 15 in order to get a paying job, his “intellectual” side was also catch-as-catch-can, the result of compulsive reading and of sitting in as a non-matriculated student at Columbia and New York Universities. Unfortunately, he also picked up his snobbism there as well which, when added to his low opinion of people as a whole allowed him to consider himself intellectually and morally superior to everyone he met—including the musicians in his band. Shaw looked down on almost everybody, which is why musicians seldom stayed with him very long. The day after he “retired” from music for the second time, in November 1939 when he fled to Mexico, Glenn Miller called up Jerry Gray and hired him as a staff arranger. Years later, when asked about it, Gray’s response was typical of just about everyone who ever played for Shaw: “I was happier musically with Artie, but happier personally with Glenn.” Tenor saxist Jerry Jerome, who had also played in the big bands of Glenn Miller and Red Norvo, was a member of Shaw’s early-‘40s band as well. His comment about the leader was:

I still wonder whether part of it wasn’t just some need to see himself as above being just a musician. He didn’t want to be on the plane of ordinary people; he wanted to be an intellectual, in the worst way.

Of course, his most famous sarcastic comment, which he himself didn’t see at all that way, was made to rival Benny Goodman who, when he met him, began asking about what reeds he used to get such great control of his instrument. “You know what your problem is, Benny?” Shaw asked him, then giving the answer: “You play the clarinet. I play music.” In later years, repeating this incident, Shaw added, “He looked at me kind of oddly as if the idea never occurred to him. He just couldn’t see that he was hung up on technique as such and not as concerned with the musical results. But I don’t think he was a very deep thinker.” One more shot at Benny after he was gone and couldn’t defend himself.

At the end of 1942 he, like Glenn Miller, disbanded in order to help the war effort in the armed forces. Miller went into the Army Air Force; Shaw went into the Navy, but was just giving concerts stateside near the training bases. Upset, he went AWOL and travelled to Washington to talk to one of the top Admirals, telling him he wanted to go where the action was. He was quickly commissioned to the South Pacific, where he played on aircraft carriers with his band. By 1944, however, he was suffering from shock and battle fatigue and had to be released on psychological grounds. After a couple of months, he formed another great band, this one without strings but featuring more innovative arrangements by Conniff, Buster Harding and Eddie Sauter.

Yet even while in the Navy, Shaw continued his high-handedness towards his musicians. In one of his short stories, obviously based on a real event, an incognito bandleader (obviously Artie) is talking to one of his trumpet players on a ship at night. Instead of encouraging him, the leader is planting seeds of concern and worry in his mind, telling him that after the war is over things aren’t going to be the same stateside, that he’ll probably have trouble finding work, and then what will he do for a living? It’s exactly the kind of incident that Shaw thought was terribly funny but the recipient of his sarcasm found deeply disturbing—yet another example of his sociopathic tendencies. Many people, reading this story, thought that the trumpet player was probably Max Kaminsky, the great trad-jazz musician who could also play swing. Decades later, when I became somewhat friendly with Kaminsky by phone, he admitted that it was indeed he. And he wasn’t amused.

Years later, asked if he didn’t think it was a tragedy that Glenn Miller had died in the war, he just had to get another shot in with a comment he again probably thought was funny. “I wish that Glenn Miller had lived,” he said, “and Chattanooga Choo Choo had died.” In 1992 he added, “Maybe I should just drop dead—it would be a good career move. Look what it did for Glenn Miller.”

Shaw’s almost pathological need for attention and to be famous probably had a lot to do with his multiple marriages, particularly to beautiful actresses who were so far from his intellectual level that he must have known they would fail, particularly to Ava Gardner but also to Lana Turner, Kathleen Winsor, Doris Dowling and Evelyn Keyes, all of which ended in divorce, some quite quickly. Asked about this in later years, he pulled out the old Jewish-male excuse: “Hey, when I was young I was a good-looking guy. The ladies wanted me and I was flattered,” to which he added, “If you want to attract beautiful women and you’re a good-looking stud, learn to play an instrument and get yourself a band. It’ll make you irresistible.” But what good did it do him to marry “trophy wives” just for the sake of getting your name splashed in the media for doing so? And he later transferred his eventual loathing of these women to the children he had by them, refusing to contact or see them as they grew up. “Why should I bother?” he said. “I didn’t get along with their mothers, why should I try to get along with them?” Everything was always about Artie. No one else in his life existed as far as he was concerned.

Ava Gardner and Artie Shaw in 1946. Just examine the snide, pompous look on Shaw’s face. It says it all.

Although none of this affected his clarinet playing, which remained spectacular throughout his career, it did affect his musical product. Following the demise of his “arranger’s band” in 1945, he next formed a particularly dreary orchestra right about the time he divorced Gardner and married Winsor. Nearly everything they played was MOR garbage with a few exceptions: two pieces by Buster Harding, The Hornet and The Glider, and a particularly excellent arrangement (I don’t know by who) of What Is This Thing Called Love? The latter was one of a handful of records that he made with one of the hippest jazz vocal groups of all time, Mel Tormé and the Mel-Tones—but once again, Shaw later took credit for this as if it had been his idea when in fact it was instigated by Walter Gross, the A&R executive of Musicraft records for which Shaw recorded at the time. The Mel-Tones were never hired by Artie Shaw. They were not a part of his band; they did not tour or do broadcasts with him. They just made the records.

After divorcing Kathleen Winsor in 1948, being temporarily single again, Shaw formed his greatest big band the following year, a mostly-bebop outfit with arrangements by Al Cohn and other gifted musicians. He adapted his playing style to bop with great alacrity, having already been a pioneer during the Swing Era in his use of extended chords and rather tricky chromatic passages which he threw into his solos. It was undoubtedly the artistic pinnacle of his career as a jazz musician, but audiences hated it. They disbanded after only five months. Interviewed in 1992 for the release of Artie Shaw: The Last Recordings, Rare & Unreleased, he said that “The 1949 band was the real reason I got out of the music business. It was a bust! All the public wanted was Beguine and Frenesi…Jesus! It can drive you crazy.”

But if the 1949 band was his real reason for quitting, why did he hang in there for five more years? In 1950 he started one last band, and one of the earliest recordings they made, in January of that year, was a very advanced George Russell arrangement of the Desi Arnaz hit tune Similau. It was probably the greatest recording in terms of musical sophistication and harmonic interest that he ever made. But the rest of this band’s output was purely vanilla music, goop like Don’t Worry ‘Bout Me, I’m Forever Blowing Bubbles, Foggy Foggy Dew, I’ll Remember April, Love Walked In, These Foolish Things and even the quintessential “drunk” song, Show Me the Way to Go Home. It was a gigantic comedown for the once-proud Shaw, and during an interview before 1992, he said that this was the band that made him quit: “I had to parade and skip on the stage while playing the clarinet, wear funny hats, etc. It was demeaning.”

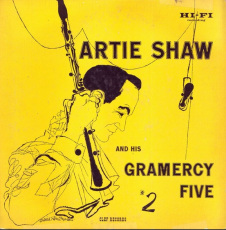

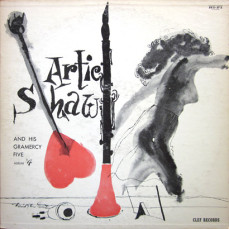

Yet during this same period, he formed what many consider to be the best of his small groups which he named “Artie Shaw and His Gramercy Five.” He took a lot of heat from musicians when it first started in 1940 because he used Johnny Guarneri on harpsichord, and this was considered to be a “gimmick,” but to be honest I’ve always loved those recordings. They had a lightness and joie-de-vivre that several of his big-band performances lacked, and the way Guarneri played the harpsichord was anything but pretentious. He replaced the harpsichord with a piano in the 1945 edition of the Gramercy Five (Dodo Marmarosa), and in the early ‘50s, after making a recording with a lineup of trumpeter Lee Castle, tenor saxist Don Lanphere, pianist Gil Barrios, guitarist Jimmy Raney, bassist Teddy Kotick and drummer Dave Williams, in 1951 he hit on a splendid combination in which he could really shine. This last version of the Gramercy Five had Hank Jones on piano, Tommy Potter on bass, Joe Roland on vibes, Tal Farlow on guitar and Irv Kluger on drums. At the very end, in June 1954, Roland dropped out and Farlow was replaced by Joe Puma.

When the MusicMasters CD of this group was issued in 1992, the cover focused on the word “unreleased,” giving many collectors—myself included—the impression that no one wanted too issue poor Artie’s best small-group performances during his active career, but this was not the case. In addition to two 7-inch vinyl 78s being issued by the small Bell Records company in 1952 (Besame Mucho b/w That Old Feeling and Tenderly/Stop and Go Mambo), Norman Granz’ Clef label issued no less than FOUR 10” LPs of this Gramercy Five. But the über-proud Shaw was undoubtedly embarrassed that he had to resort to a cheapo label (Bell) and a jazz speciality label (Clef) rather than having them issued by Decca or RCA.

When the MusicMasters CD of this group was issued in 1992, the cover focused on the word “unreleased,” giving many collectors—myself included—the impression that no one wanted too issue poor Artie’s best small-group performances during his active career, but this was not the case. In addition to two 7-inch vinyl 78s being issued by the small Bell Records company in 1952 (Besame Mucho b/w That Old Feeling and Tenderly/Stop and Go Mambo), Norman Granz’ Clef label issued no less than FOUR 10” LPs of this Gramercy Five. But the über-proud Shaw was undoubtedly embarrassed that he had to resort to a cheapo label (Bell) and a jazz speciality label (Clef) rather than having them issued by Decca or RCA.

One thing I’ll give to him, though: in that last year his once-flourishing mane of hair had gone but he just continued to play and appear balding and made no attempt to cover it up with a wig. And another thing I’ll be the first to give him credit for is that it was an insult for some music critics to claim that because his improvisations sounded so perfect that he wrote them out in advance. In addition to comparing airchecks vs. studio recordings from the 1938-49 period, one can also compare the Bell recordings to the same pieces recorded by Clef to see how he changed his solos. The bottom line is that those who wrote that about him were jealous of his talent, which was formidable. If you listen to ANY modern-day clarinetist play his Concerto for Clarinet, for instance, you’ll note that not one of them can combine his fluidity of both swing and a full tone. They either play “out” and fudge the triplets and turns or, more often, they reduce the volume in order to get through those passages without making a mistake.

One thing I’ll give to him, though: in that last year his once-flourishing mane of hair had gone but he just continued to play and appear balding and made no attempt to cover it up with a wig. And another thing I’ll be the first to give him credit for is that it was an insult for some music critics to claim that because his improvisations sounded so perfect that he wrote them out in advance. In addition to comparing airchecks vs. studio recordings from the 1938-49 period, one can also compare the Bell recordings to the same pieces recorded by Clef to see how he changed his solos. The bottom line is that those who wrote that about him were jealous of his talent, which was formidable. If you listen to ANY modern-day clarinetist play his Concerto for Clarinet, for instance, you’ll note that not one of them can combine his fluidity of both swing and a full tone. They either play “out” and fudge the triplets and turns or, more often, they reduce the volume in order to get through those passages without making a mistake.

But the Concerto for Clarinet is a prime example of Shaw’s need for public love vs. his artistic instincts. When he was asked to write the piece for his Paramount film with Fred Astaire, Second Chorus, he was sceptical and eventually dismissive of the results, which he said were just “a couple of good riff tunes held together by pseudo-classical passages,” but once the sales of the recording took off he embraced it as one of his best records—largely because of the spectacular finale in which he played an altissimo high C. But so what when that high C followed nearly a half-minute of pretentious quasi-classical devices? Similarly, his 1953 Decca recording of These Foolish Things is mostly just clarinet-with-mushy strings in the accepted MOR style of the day, but suddenly, at the end, the orchestra stops and he plays a spectacular 11-bar cadenza, topped off by yet another “impossible” high note, which he later said was the high watermark of his entire 30-year career as a clarinetist, “the only time I played exactly what I wanted to and it came off perfectly.” But it still follows a banal performance of These Foolish Things.

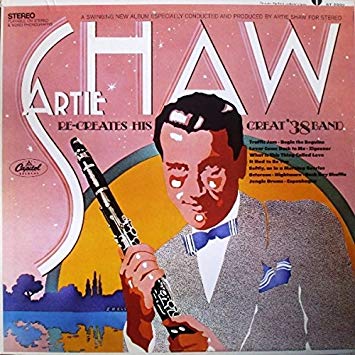

When Shaw retired at the end of 1954, he turned his clarinet into a lampstand and became a real estate broker. He did good business for a few years due to name recognition, but eventually business dropped off and he stopped that as well. In 1968 he allowed Capitol Records to assemble a band and make a stereo album titled Artie Shaw Re-Creates his Great ’38 Band, but he didn’t pick the musicians or direct it; he just gave his approval to release the takes. He was very happy with it because clarinetist Walt Levinsky did a superb job of emulating Shaw’s tone and technique, and drummer Don Lamond did a near-perfect Buddy Rich imitation. By this time, however, he was busy writing, mostly short stories, of which two volumes were published. As Terry Teachout put it in his March 2005 article on Shaw in Commentary, “Music’s loss was not literature’s gain,” his writing being “the work of an intellectual manqué, an autodidact eager to show off his hard-won knowledge. Unfortunately, Shaw had little to say about anything other than himself—he was in private life a garrulous, self-obsessed monologist—which undoubtedly explains why he had no success as a writer of fiction.”

When Shaw retired at the end of 1954, he turned his clarinet into a lampstand and became a real estate broker. He did good business for a few years due to name recognition, but eventually business dropped off and he stopped that as well. In 1968 he allowed Capitol Records to assemble a band and make a stereo album titled Artie Shaw Re-Creates his Great ’38 Band, but he didn’t pick the musicians or direct it; he just gave his approval to release the takes. He was very happy with it because clarinetist Walt Levinsky did a superb job of emulating Shaw’s tone and technique, and drummer Don Lamond did a near-perfect Buddy Rich imitation. By this time, however, he was busy writing, mostly short stories, of which two volumes were published. As Terry Teachout put it in his March 2005 article on Shaw in Commentary, “Music’s loss was not literature’s gain,” his writing being “the work of an intellectual manqué, an autodidact eager to show off his hard-won knowledge. Unfortunately, Shaw had little to say about anything other than himself—he was in private life a garrulous, self-obsessed monologist—which undoubtedly explains why he had no success as a writer of fiction.”

Tom Nolan, of course, simply loved the guy and makes excuse after excuse for his behaviour. He never saw his children grow up? He never called his friends directly to talk to them, but had a factotum phone them and announce, “Please hold. Artie Shaw wishes to speak to you”? Well, he was just very private and shy, you know. But the man’s pettiness went far beyond that. I still remember a time, back in the 1990s, when some American record collector ran across one of Shaw’s rarest records, an English Brunswick 78 of his 1949 band. Apparently, the local newspaper and TV station had nothing better to report that day, so his find hit the news. A few days later, he got one of those “Please hold. Artie Shaw wishes to speak to you” calls. He was thrilled, assuming the great man wanted to congratulate him. No such luck. Shaw told him that he didn’t have a copy of that record, that it was his intellectual property, and if he didn’t send it to him—gratis, mind you, no reimbursement—he would sue him. Even Tom Nolan can’t explain that one by claiming shyness or a persecution complex.

Some great artists are simply jerks. Gesualdo was one; so too were Benvenuto Cellini, Richard Wagner and several others. Artie Shaw fits into that category. We just have to “disremember” his foibles and incredibly crass statements when enjoying his recordings, which are clearly the product of a supreme master of his instrument.

You can read more in detail about Shaw’s good and bad musical judgment in my online book, From Baroque to Bop and Beyond: An extended and detailed guide to the intersection of classical music and jazz

Last modified: July 18, 2019