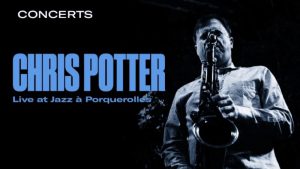

In this new project, Chris Potter continues to explore groove and presents new variations on his abiding ambition to “connect jazz to the dance music of the day without sacrificing substance.”

Here, Potter presents a different take on the acoustic ECM albums and on the plugged-in, groove-and-texture-saturated environment that he navigated during the latter half of the ’00s with keyboardist Craig Taborn, guitarist Adam Rogers, and drummer Nate Smith in Underground, the highly influential, experimentally-oriented unit that generated three recordings between 2005 and 2009.

This 9-tune date showcases one new partner — the brilliant 23-year-old keyboardist-acoustic pianist James Francies — and one of long-standing — drummer Eric Harland. Virtuoso electric bassist Linley Marthe contributes his singular groove conception to four selections.

What’s the gestation story for the Circuits band?

In a way, it fell into my lap. It had been in my mind for a while that I wanted to do something again in the more groove-ish realm, but with a different sound and focus than Underground. Then in the summer of 2017, I did a short tour in Europe with Eric Harland, who I’ve worked with in many situations for many years, and James Francies, who I hadn’t met. Eric recommended him to me. I had an idea of the basic musical direction — a keyboard-heavy (synth and whatever else) sound along with the acoustic piano — but I didn’t know what to expect. It worked so well and was so much fun that I felt I should document it.

![]()

Watch Chris Potter Live At Jazz in Porquerolles on Qwest TV

What qualities did James bring to the table that made it a different experience than Underground, where you were interacting with Craig Taborn?

It’s hard to put exactly into words. James is twenty-three, and I could feel that he has a different generational take on things. It’s hard to quantify exactly what that is, but I remember when I was twenty-three, playing with older people, and could see that they had come up listening to a different set of things, and I could learn a lot from them. Now, as a more established musician, I see it from the other point of view – I can definitely learn from the younger generation. I hear how James has grown up not only listening to the things I listened to when I was coming up but also all the things I’ve done and my peers have done, which has influenced his music. Also, hip-hop already existed when James was born, and his sonic choices and approach are informed by that in a way that’s hard to describe, but puts it in a different zone.

Did his tonal personality have an impact on the writing you did for the group?

No, because I didn’t know what he’d sound like. I wrote the music over the course of maybe three weeks before that summer 2017 tour, because we had to play something. We rehearsed once right before we left, and then did the tour. It’s very nice to know exactly who will be playing, know everything about how they work, but this wasn’t one of those situations. But what I wrote, James interpreted very well and brought his own thing to it.

The writing always takes on a life of its own depending on who’s playing it. When I’m writing a tune, I always have an idea of the direction I want, but I find that the results are always better if I’m willing to go away from that once I hear it. So even though I did all the writing before hearing how it would sound, it fits well with what James was doing, and the end product has his stamp on it as well.

You mentioned your long history with Eric Harland, who is also part of that equation — both he and Nate Smith, your drummer in Underground, have distinctive conceptions of a groove. Can you speak to Eric’s contributions?

That’s probably one reason why the writing worked as well as it did and why it was so easy and comfortable to slide into this new situation. I do know Eric’s playing very well, and I could imagine how he would approach things. I trust his aesthetic instincts. Whatever is going on, he always makes music out of it. I also know that he’s able to deal with whatever meters I want to throw at him. That gave me a lot of freedom.

When composing, are you thinking of your own sound first and foremost?

When it’s working at its best, it’s on an unconscious level. If you think too much about it, you might over-think what it should be. I notice that I like to write a batch of tunes. I like to think of it not as one tune at a time, but as a set, an album, that needs some highs and lows, some fast and slow, one mood here, another mood there.

We also played James’ tune, “Pressed For Time,” at the end of the album, and “Koutomé,” which came from a recording by a group from Benin called L’Orchestre Poly-Rythmo de Cotonou, which Lionel Loueke told me was a big influence on him growing up. It’s a very simple tune, but deceptively hard to play over, with a different groove than I’d ever heard. I thought it would be interesting to bring it in, as a contrast to some of the denser music.

Sounds like a similar process to your approach on albums like Imaginary Cities or The Sirens or The Dreamer Is The Dream, where you followed a certain narrative thread. Is there a narrative to Circuits, and if so, how would you describe it?

This does not have a literal narrative. With Imaginary Cities and The Sirens, I had a certain idea where the moods of the tunes would come from. This is more abstract. It’s just a sound.

More about the joy of playing?

Yeah. I did conceive it as fun music. There’s some darkness in there, too. But I wanted it to be fun to play and fun to listen to.

It occurs to me that during the years since you wrote extensively for Underground, you’ve done a deep dive into composing orchestral music. I’m wondering in what ways your pursuit of those interests inflects what you did on Circuits.

This is the only situation so far where I did the whole production myself. We did a live performance at GSI Studio in Manhattan, which Eric has a strong involvement with, and then I took it home, where I could overdub whatever I wanted on my limited studio, on my own time. It keeps the energy of a live performance record, but I added things to make it more exciting, more fleshed out. I didn’t necessarily add much that wasn’t already there in the composition; it’s more that I orchestrated things that were already written in that you might not notice unless they were doubled. So I went nuts with woodwinds and guitars and keyboards, and I used some gong and more samplers and so on. It was super fun.

To what extent is the music you write for one project or set of personalities interchangeable with another group or configuration? Would this music suit your acoustic quartet with David Virelles, Joe Martin and Marcus Gilmore? Would it suit Underground?

I’m sure that we could play the same tunes with all these groups, and it would work, and each one would have a different thing. But I like to keep separate books; I like to keep a particular set of music to give a certain band its identity. It means writing a lot of music and generating a lot of tunes. I enjoy that process, and I think helps my musical growth.

You’ve been composing seriously during most of your career as a recording artist, and I think you first did this kind of layering when you were signed with Concord, during the 1990s.

I did some doubling of the woodwinds even on Concentric Circles, which I recorded in 1993 – very early on. But I couldn’t fully explore that idea without being able to do it at home, which enabled me not to consider the studio time. Here I had a chance to try a bunch of things, make mistakes, throw them out, and then do it a different way, which you can’t do when you’re standing there and you know it’s costing a lot of money and you only have three hours left.

Anything you can say about your ambitions as a composer?

I’ve always looked at writing as another way to express my musical personality. It’s let me set up a lot of situations that will challenge me to grow as an improviser. The two processes are two sides of the same thing — the writing affects how I think about improvisation, and vice-versa.

A lot of my writing has been for smaller groups, where the art is to have just enough material to create something to work from, but not too much, so you give yourself room to do different things as an improviser. Maybe I’ll set up some kind of melody (obviously a strong melodic focus); a mood; maybe some rhythmic cycle that’s challenging but has a certain groove that I couldn’t do any other way. Then I go out and play it. The idea is to try to write something that’s not only fun to play the first time but is still fun to play the 30th time and maybe even the 60th time — or more. That’s what’s hard, I think. The Wayne Shorter tunes from the 1960s, and Ornette’s music, and Monk’s music are examples of very durable tunes that you can play again and again and again. I’ve always wanted to be able to write tunes that are that durable.

Writing for large ensembles is a different thing, where it’s possible to flesh out and explore your musical ideas more thoroughly. Every time I embark on a larger ensemble project and am really scoring things out, I get the feeling that I’m growing by seeing things from an eagle-eye view. Writing for the large ensemble is especially time-consuming. But I spend that time very focused on making musical decisions about how a tune should start, where it should go next, making sure I dot every “i” and cross every “t” and everything has some kind of harmonic logic, even if it’s not standard logic — that all the moving parts work together. It’s played a part in my growth as a musician.

Any future, as-yet-unrealized projects in mind?

More and more playing. I’m working on a kind of big band. I’m not sure exactly who-what-where-when. The accent is on a Gil Evans sound, an ensemble with french horn and tuba and woodwinds, along with singing — music with voice and words, which I’ve taken from various poems. It’s pretty much sketched out, but the arrangements aren’t quite done. I was able to perform some rough drafts in the fall with a group at the Royal Academy of Music.

I’ve also written another batch of Circuits tunes, which we’ll probably start investigating when we’re out on the road to see what’s there. The trio is about to do a North American tour that will be pretty intense, and then I’ll go to Europe in March and April with a quartet version of Circuits with Craig Taborn, Tim Lefebvre and Justin Brown. The tour was already set up, but it turned out that neither James or Eric could make it. It will be very different-sounding with them, but it might turn out great. Then I might think, “Wow, this should be another band.”

This Interview was first published by Qwest TV in March 2019.

Last modified: August 7, 2019