On 30 March, 1970 the jazz world was rocked with the release of Miles Davis’ album Bitches Brew. The album proved to be a huge commercial success selling well over a million copies and delivering Miles his first Gold and Platinum Records. The album was awarded a Grammy in 1971 for “Best Large Jazz Ensemble Album” and according to RIAA sales data, Bitches Brew is still to this day in the Top 10 best selling jazz albums of all time.

Reception

The impact of the Bitches Brew Album was seminal to the development of jazz in the 1970’s and it’s force can still felt today. As journalist Michael Segell wrote in 1978, jazz was “considered commercially dead” until this album’s success “opened the eyes of music-industry executives to the sales potential of jazz-oriented music”.

Langdon Winner of Rolling Stone magazine, wrote in one of the albums first major reviews, “The freedom which Miles makes available to his musicians is also there for the listener to hear. If you haven’t discovered it yet, all I can say is that Bitches Brew is a marvellous place to start. This music is so rich in its form and substance that it permits and even encourages soaring flights of imagination by anyone who listens. If you want, you can experience it directly as a vast tapestry of sounds which envelop your whole being”.

Village Voice critic Robert Christgau deemed it “good music that’s very much like jazz and something like rock”, naming it the year’s best jazz album and Davis “Jazzman of the year” in his ballot for Jazz & Pop Magazine.

According to independent scholar Jane Garry, Bitches Brew defined and popularized the jazz fusion genre, also known as jazz-rock, however, it was hated by a number of purists. The infamous jazz critic Stanley Crouch (who was once fired by the Village Voice for throwing someone through a window) has never warmed to the seminal double LP, describing it as “Formless” and in a 1991 column for The New Republic, “The most brilliant sell-out in the history of jazz”.

Another jazz critic and producer, Bob Rusch, wrote in the ‘All Music Guide to Jazz’ (1994), “This to me was not great Black music, but I cynically saw it as part and parcel of the commercial crap that was beginning to choke and bastardize the catalogues of such dependable companies as Blue Note and Prestige… I hear it ‘better’ today because there is now so much music that is worse.”

It was not only the critics that were vocal as to the music contained on the album, Donald Fagen of Steely Dan fame described the album as “just a big trash-out for Miles”. He added “To me it was just silly and out of tune, and bad. I couldn’t listen to it.” He went on to say “It sounded like (Davis) was trying for a funk record, and just picked the wrong guys”. A personal anecdote comes from my father, a huge Miles Davis fan, who said after his first listen “Well, jazz is now officially dead” – A statement he later in life retracted stating he may have been rash in his commentary. While my father may be just one voice it was a sentiment shared by many jazz fans at the time. One thing for sure, the album did divide the jazz public firmly into two camps.

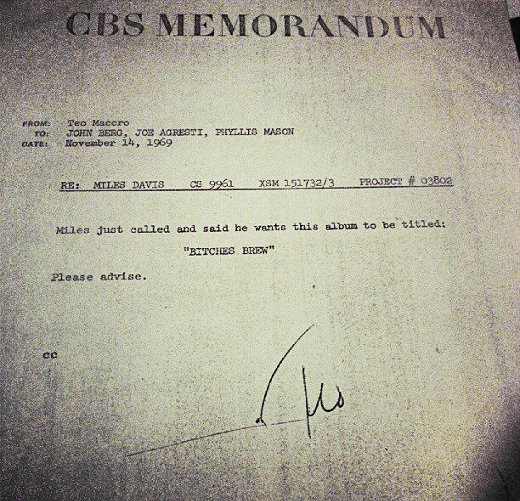

The album was controversial even prior to it’s 1970 release. In a memo written in November of 1969 by producer Teo Macero to Columbia Records executives John Berg, Joe Agresti and Phyllis Mason asking for advice from “up stairs”, Macero wrote the following:

“Miles just called and said he wants this album to be titled: “BITCHES BREW” – Please advise.”

One can only imagine the panic at CBS Headquarters. However needless to say the album was released, title unchanged.

A view from the inside.

In July of 2017, Paul Tingen, a Miles Davis scholar and author of “Miles Beyond, The Electric Explorations of Miles Davis, 1967-1991” wrote an extensive article with an extended analysis of the making of Bitches Brew. The full article has been published on the JazzTimes website. Tingen’s article not only sheds light on the production process, it also puts the album fully into a historical context and while it’s a rather extensive article, it’s worth setting aside the time to read.

The production of Bitches Brew was not a complete new direction for Miles, however, it was more of a continuation of a direction that he had embarked on some years earlier. This is evidenced by the album “In A Silent Way”. In Quincy Troupe’s biography, Miles himself described the sessions as an organic creative process “I would direct, like a conductor, once we started to play, and I would either write down some music for somebody or would tell him to play different things I was hearing, as the music was growing, coming together. While the music was developing I would hear something that I thought could be extended or cut back. So that recording was a development of the creative process, a living composition. It was like a fugue, or motif, that we all bounced off.”

In Darrell Craig Harris’s interview (also in this magazine) bassist Dave Holland commented when speaking about the recording “With Miles there was a very free feeling to the whole process. There was definitely material, but it was a minimalist kind of thing – a melody here, bass line there and we just start things going, well, Miles would just get things going and then as we were recording, he might point to Wayne or just look at Wayne and he would start soloing. It had this very loose and free kind of thing and, of course, that comes through in the music. It was sort of searching as well, somehow the keyboard players were all trying to figure out how to make it work with multiple keyboards. Miles created this setting where it all came together.” Drummer Jack DeJohnette also stated, “It was different and it was fun. There wasn’t a lot said. Most of it was just directed with a word here and a word there. We were creating things and making them up on the spot, and the significant thing was that the tape recorder was always rolling and capturing it.” This all certainly seems consistent with Miles’ words above.

Not all of the creativity on this album happened during the sessions, producer Teo Macero played a critical role in the albums production, however, not from the point of view one would expect, given the traditional role of a producer. In the case of Bitches Brew Macero’s influence on the final product came largely in post production.

Joel Lewis, in his article “Running the Voodoo Down”, published in The Wire (1994), relayed that Marceo explained when asked about the editing process “I had carte blanche to work with the material, I could move anything around and what I would do is record everything, right from beginning to end, mix it all down and then take all those tapes back to the editing room and listen to them and say: ‘This is a good little piece here, this matches with that, put this here, etc., and then add in all the effects—the electronics, the delays and overlays. I would be working it out in the studio and take it back and re-edit it—front to back, back to front and the middle to somewhere else and make it into a piece. I was a madman in the engineering room. Right after I’d put it together I’d send it to Miles and ask, “How do you like it?’” And he used to say, “That’s fine,’ or ‘That’s OK,” or “I thought you’d do that.” He never saw the work that had to be done on those tapes. I’d have to work on those tapes for four or five weeks to make them sound right”.

Paul Tingen relays in his article that “Publicly, Miles rarely acknowledged Macero’s role. He mentioned the producer just a few times in his autobiography, and only in passing. It’s not hard to suspect that this may have had to do with their love-hate relationship, exemplified by Miles’ refusal to talk to Macero for more than two years after the producer was involved in the release of ‘Quiet Nights’ in 1964.”

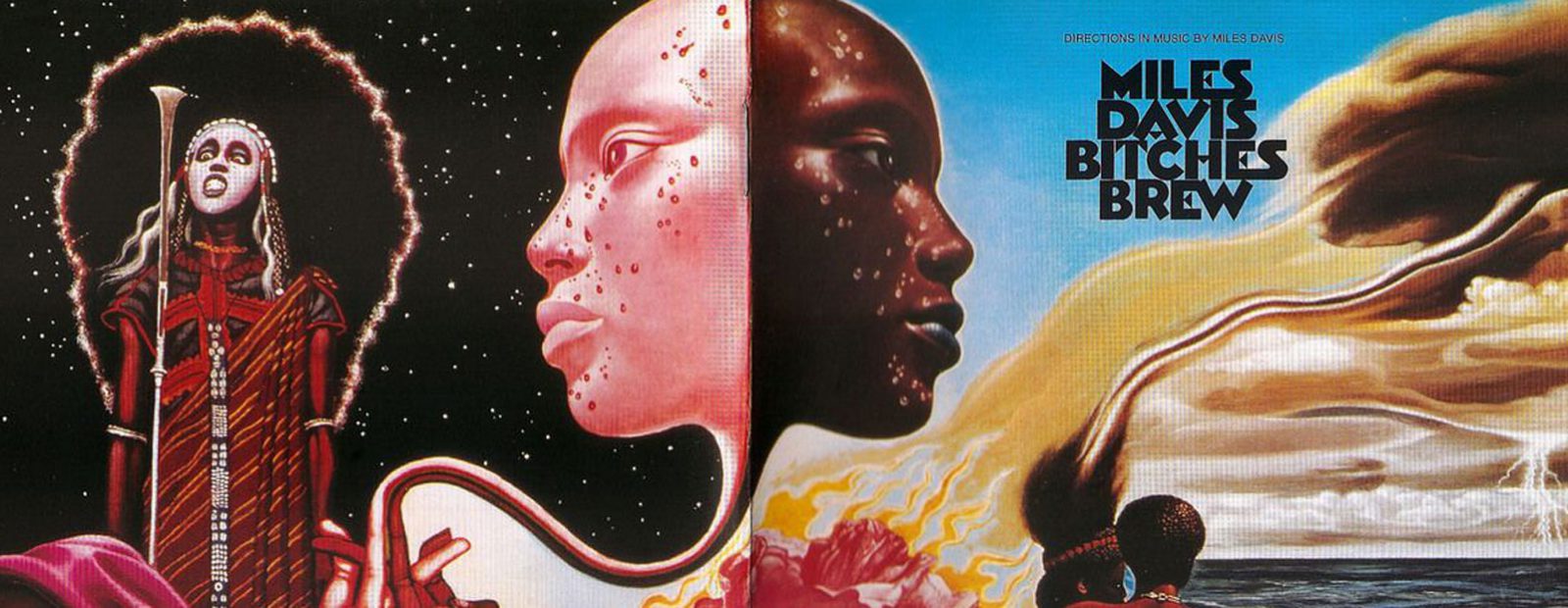

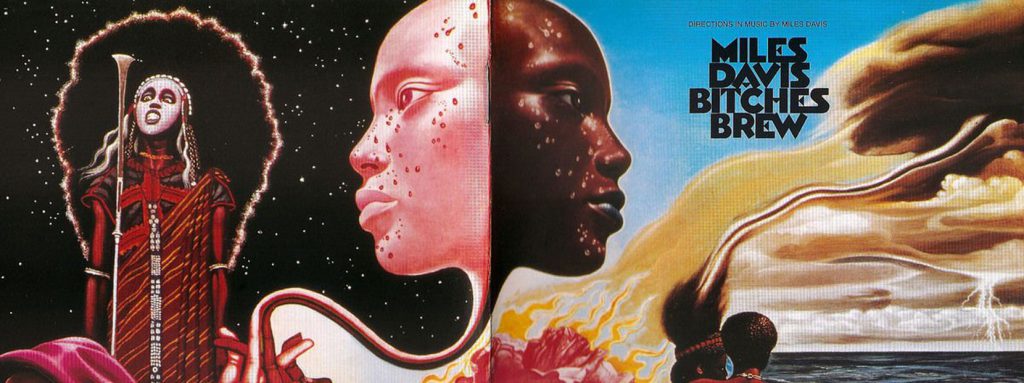

Cover Art-Work

It was not just the music or album title that created controversy. Mati Klarwein, the artist that Miles commissioned to create the cover art also metaphorically “poked the bear” of American society. At the time of Bitches Brew’s release, racial tensions in the United States were still high and Klarwein’s image of black and a white woman intertwined across its spine has been commonly interpreted as a comment on these racial divisions.

Klarwein was himself seen in the art world as a controversial figure. Born in Hamburg in 1932, to a Jewish architect father from Polish origins and a German mother, the three fled to Palestine when he was two years old after the rise of Nazi Germany. After the war Mati and his mother moved to Paris where he enrolled at the “Acadèmie Julian “, having previously dropped out of school in Israel and been sent at the age of 15 to an art college in Jerusalem. He moved to New York in 1965. By then his work was considered to be inspired by surrealism and the so-called psychedelic movement of the time. The surrealistic rendering on the cover of Bitches Brew would now seem to be an ideal, and perhaps, a genius parallel to the revolutionary music contained within its sleeves. The original artwork renderings were sold in the 1970s and it’s said that Davis tried, unsuccessfully, to track it down and buy it the following decade.

Now 50 years after the release of Bitches Brew, this album still holds pride of place as one of the most influential jazz recordings of all time.

The following Video was recorded on the 18th of August 1970 at Tanglewood and presents Bitches Brew live.

Line-up:

Miles Davis, Trumpet | Gary Bartz, Alto & Soprano Saxophones | Chick Corea, Electric Piano | Keith Jarrett, Organ | Dave Holland, Bass | Jack DeJohnette, Drums | Airto Moreira, Percussion

![]()

Jazz In Europe Magazine – Spring 2020 Edition

This article also appears in the Spring 2020 edition of the Jazz In Europe print magazine.

Also included in this edition are interviews with Cyrille Aimee, Ray Gelato, Dave Holland, Jason Miles and Sem van Gelder. We take a look at Bitches Brew, 50 years on. Tony Ozuna presents us with a look at the Czech jazz scene from it’s origins behind the Iron Curatin to the present day. This editions photo feature spotlights British photographer William Ellis.

Also included in this edition are interviews with Cyrille Aimee, Ray Gelato, Dave Holland, Jason Miles and Sem van Gelder. We take a look at Bitches Brew, 50 years on. Tony Ozuna presents us with a look at the Czech jazz scene from it’s origins behind the Iron Curatin to the present day. This editions photo feature spotlights British photographer William Ellis.

You can purchase a copy of the magazine here.

Last modified: July 19, 2020