This piece was first published by Lynn Rene Bayley on her blog “The Art Music Lounge“

I’m sure this opinion will astound some readers and rile others, but in my personal opinion Clifford Brown (October 30, 1930 – June 26, 1956) was the greatest jazz trumpeter who ever lived. Bar none. And more to the point, he was in many ways the Bach of jazz. This may seem like a rash judgement (or, at least, an emotionally informed one) to those who think of jazz pianists as being closer to Bach; but not even the great Jacques Loussier, who has made a lifetime’s work of combining Bach and jazz, has ever surpassed on the keyboard what Clifford Brown did on his horn.

And what, you will certainly ask, is Bachian about Brown’s playing? To my ears, it is his consistently structured playing in which every note builds the phrase, every phrase builds the solo, and each of his solos within a tune comprises a piece of an overall structure. Granted, he uses intervals and smeared notes indigenous to jazz music and not within the vocabulary of J.S. Bach, but that is not the point. Listen carefully to each of his solos—particularly his last session performance of A Night in Tunisia—and tell me that the overall construction is not like Bach.

Brown was a superb melodist and could, in fact, play mellifluous solos without his famed double-time runs and fills, but more often than not his playing was contrapuntal and mathematically logical—two of Bach’s hallmarks—and never failed to fulfill the promise he held out to his listeners once he embarked on an improvisation.

Of course, being a jazz musician Brownie’s solos were full of surprises: not only the bent and blue notes, but also unexpected leaps upward and downward throughout the range. Although, like all jazz musicians, his musical imagination occasionally led him to flub a note here and there, Brown’s rock-solid technique precluded any real breakdowns. Most of the time, every note he wanted to play was at his lips and fingertips. He didn’t have to worry about technique because the technique never really failed him. Whatever was in his mind came out of his horn, and what came out of his horn was both inaginative and logically built.

Listen to his famous 1953 recording of Cherokee, for instance—which just happened to be the first record I ever heard by him—and you’ll see what I mean. Brown never once plays the melody straight; from his very first entrance he is busy playing eighth and sixteenth-note runs, filling space the way Bach filled space in his keyboard works, and like the violin partitas and cello suites, Brownie sometimes played his own counterpoint to his melodic ideas, thus completing the musical structure in a way that was fulfilling emotionally and intellectually. Then follow Cherokee with the orchestrated version of the tune, the Paris Big Band performance now retitled Brownskins. Here, as in Bunny Berigan’s famous performance of I Can’t Get Started, Brown creates a slow, ballad-tempo introduction before launching into the fast part of the piece. And even in this slow introduction, Brown is thinking ahead in terms of structure and substance, so that this introductory preface is more than a mere curtain-raiser. It is an integral part of the piece to come.

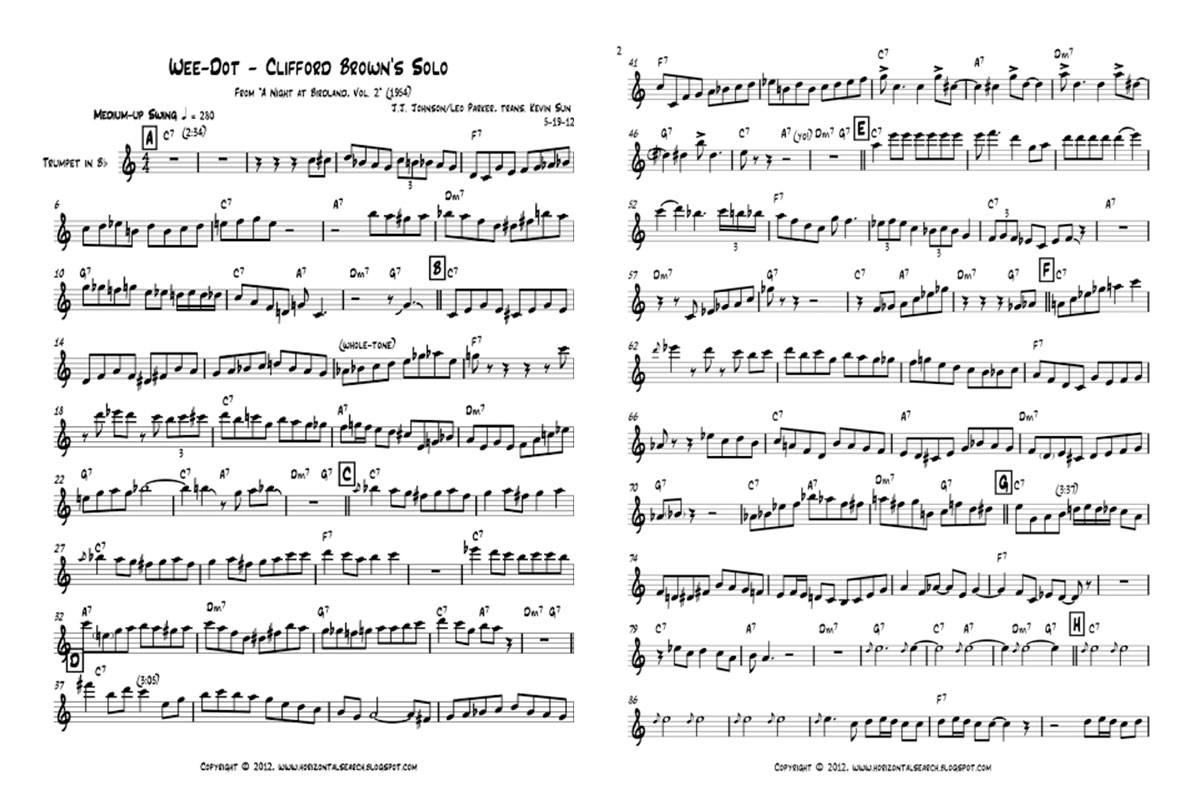

If you examine the first two pages of his solo on the 1953 performance of Wee Do, for example, you will notice the almost mathematical precision with which he constructed his work. Even when a rapid series of accidentals or whole-tone scales are used, Brown’s musical thought continues to carry him beyond the moment. I’m convinced that his musical thinking was at least four to eight bars ahead of where he was at any given time; he was therefore creating spontaneous, logical compositions when he soloed, not just a few phrases followed by a few more phrases.

You can hear this solo click here.

I’ve heard every recording Brown ever made and own most of them. The only one I no longer have is the “Clifford Brown with Strings” album, and the reason I don’t have it any more is that it is the least impressive of his records. Here, Brown wasn’t trying to play in a particularly inventive way, but rather to create a mood music album. He succeeded in this, but it wasn’t him. I think he knew it. To me, it doesn’t even sound as if he’s playing with any heart. And this was certainly not characteristic of Brown; if anything, in all his other recordings and live performances, playing with heart (as well as with the mind) is what attracts one to him and keeps the listener enthralled.

Charles Mingus became angry with Brown, and his former friend Max Roach, when the Brown-Roach Quintet rebuffed his request to play some of his music. Following Brown’s turn down, Mingus hired the young and then-unknown Thad Jones, who he claimed in an interview was better than Clifford. Even Thad knew that wasn’t true, good as he was. In a way, however, I understand Brown’s reluctance to play Mingus: Mingus’ music was circular, with unusual chord positions and sometimes several tempo changes. This was closer to the aesthetic of Mahler, the great late Romantic, not to the Baroque and Classic styles that informed Brownie’s playing. You can hear the difference between them in Brown’s own compositions, e.g. Daahoud, [1] Joy Spring and especially the wonderfully underrated Tiny Capers, which starts out with a mini-fugue (or round) in the opening section before moving into the looser, more improvised section. Brown’s mind just worked in a different way, musically, from Mingus’. They were contemporaries in the same timeline but quite different musically.

So the next time you listen to a Clifford Brown recording, please listen carefully. Listen for the structure, the way he builds his solos, the way he occasionally plays his own counterpoint; and then listen for some of these same qualities when he is improvising within an ensemble. Once when discussing trumpeters with one of my closest friends, the late trad jazz clarinetist Frank Powers, I asked him what he thought of Brownie. Being a trad jazz musician, I figured he wouldn’t like him very much, but that wasn’t the case. He said, “Clifford Brown was a genius. He could play the freaking phone book and make it sound great.” And indeed he was. I agree with you, Frank.

[1] One online post claims that Daahoud was the name of Brown’s “drug dealer,” but this is completely false. Brown made a point of being totally clean: he didn’t smoke, didn’t do drugs, and only drank in moderation. A much more believable story came from an interview with pianist Matthew Shipp, whose mother was friends with Brown, Shipp said, “Where I lived, in Wilmington, Delaware…was a guy named Daahoud, who Clifford Brown wrote the song about… this old alcoholic who still played.”

Last modified: July 15, 2018