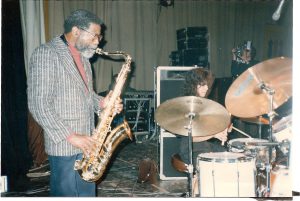

Sylvia Cuenca has built an impressive career sharing the bandstand with some of jazz’s most standout ensembles. Alongside the likes of Joe Henderson and Clark Terry, Cuenca has secured her place in New York’s most wanted jazz circle, becoming a regular in New York’s hottest clubs, as well as touring across the globe with the Joe Henderson Quartet. Her work with jazz luminaries is endless, continuing to this day alongside her music writing and important actions in the sector. She was a guest clinician at the ‘Sisters in Jazz Program’ at the International Association for Jazz Education( IAJE) Convention in NYC and the Mary Lou Williams Festival at the Kennedy Centre in Washington D.C.

Photo by Chris Drukker

It was such an honour to ask her some questions about her long, impressive career, particularly what experiences have stood out for her along the way.

Could you tell me a little about your music education and your journey to get to where you are today?

In junior high school, I took a snare drum class and fell in love with the instrument. Shortly after, my father arranged private drum lessons, and I continued private lessons through high school. In the summer of my senior year, I attended San Jose City College in San Jose, CA, which had a strong jazz program directed by trombonist/arranger Dave Eshelman. I studied theory and developed my sight-reading skills by playing in jazz combos and big bands. Around the same time, I won a scholarship to attend the Stanford Jazz Workshop in Stanford, CA. Victor Lewis, the drum instructor, had a profound effect on my playing, and he was the one who encouraged me to move to New York City to pursue my career.

After I moved to NYC in 1985, I attended Long Island University and continued my music education under director Pete Yellin. After a few semesters, I started touring and had to put my college degree on hold. When I was between tours, I continued to study privately with Victor Lewis, Adam Nussbaum, and Brazilian drummer Portinho. In 1992, I received a study grant from the National Endowment for the Arts. I chose to study with drum master Keith Copeland for one year. With Mr. Copeland, I continued to develop my 4-way independence. He also made me aware of my centre of gravity while I played, which enabled me to execute difficult techniques with both of my feet. I learned about the lineage of jazz drummers and studied the classic recordings of these drummers. In 2014, I went back to school and completed my Jazz Performance degree from Empire State University in New York City.

What was it like performing with the Joe Henderson Quartet? Could you tell me a bit more about that experience?

I first met Joe Henderson when he was a guest artist with the San Jose City College big band. Years later, when I moved to New York City, I went to hear him play at the Village Vanguard, and I reintroduced myself to him. He remembered me from California, and he asked me for my phone number. A few months later, some friends told me that Joe was looking for me. One day, I got a phone call from someone who sounded like Joe, but I thought it was someone playing a joke on me. Then I realised it was Joe and he was asking if I was available for a 3-week European tour. This was the beginning of my 4-year stint with his quartet. It was also my first time in Europe, and it was some of the best years of my life. We toured and performed at various clubs, concerts, and festivals both domestically and internationally.

Most of the time, he would let us interpret the music as we heard it. He wasn’t the kind of leader to give a lot of verbal direction unless it had to do with a specific figure or arrangement. He would say, “Play what you mean and mean what you play!” He made me aware of the importance of playing with conviction. Many times, he would give you a solo and the whole band would leave the stage and let you work out whatever you had to say musically. It was challenging, but it made me dig deep, and it helped me to grow as a musician. He also helped me to be mindful of the form of a song by constantly singing the melody in my head behind solos, including my own. By playing with Henderson, I learned how to be a sensitive and musical team player in a small group setting. On stage, he would never have a setlist or charts, and the band never knew what we were going to play next. We played a lot of standards like ‘All the Things You Are,’ ‘Lush Life’, ‘Ask Me Now’, ‘You Know I Care’, ‘Without a Song’, ‘Invitation’, ‘Round Midnight’, ‘What Is This Thing Called Love’, and so many others. Sometimes, he would have one-word cues for telling the band the next selection. He would turn around and say, “Lady B” for the Sam Rivers tune Beatrice or “Jin” for Jinrikisha or “Isssss” for Isfahan by Billy Strayhorn. From the tunes that Joe wrote, we played ‘Record-a-me’, ‘Y Todavia La Quiero’, ‘Isotope’, ‘Shade of Jade’, ‘Punjab’, ‘Serenity’, ‘Mode for Joe’, ‘Our Thing’, ‘Black Narcissus’, ‘Gazelle’, ‘Inner Urge’, ‘Blue Bossa’ and many other great tunes. It was a dream come true and an honour to share the stage with jazz legend Joe Henderson, and I’m forever grateful for the opportunity.

Photo by Chris Drukker

You have also played with several other huge names on the scene. Do you have a moment in your career that particularly stands out to you?

I’ve been very fortunate to experience many moments that stand out in my career so far. I’d like to share a few of them with you. Since I started playing this music, I have intensely listened to and studied the music of both Joe Henderson and Clark Terry. Each of them has a very distinct and easily recognisable voice on their instrument…. something that we all strive for.

The most incredible musical moments that I’ve ever experienced were when I had the opportunity to share the stage with these two iconic jazz artists. It was exhilarating to know their sound in my head from recordings and then look up and realise their sound was coming out of their horn right in front of me and that they trusted me to share the bandstand with them! I’ll treasure these moments for the rest of my life.

One evening, I was at home, and I got a call from a trumpet player friend of mine, Eddie Allen. He told me that the drummer didn’t show up for the gig. It was a week-long engagement with the legendary saxophonist/composer Frank Foster’s Loud Minority Big Band at the Jazz Standard in NYC. He asked me how soon I could get to the club with my drums and play with them. I jumped up and loaded my drums in my car and rushed over to the Jazz Standard. When I got there, the big band (of some of the best musicians in NYC) were on stage, ready to play, and they were just waiting for me to set up my kit. Sweating and out of breath, I stayed focused and sight-read the infamous, challenging compositions and arrangements by Frank Foster. It wasn’t perfect, but I guess it was ok because he asked me to play the rest of the week, which included a live recording of the big band. It was proof that you never know what can happen in NYC and that you should be ready for anything at any time!

Another time, I was playing a week-long gig at the Village Vanguard with the Clark Terry quintet. I had my eyes closed on this one tune, but when I opened them, I looked on the bench beside the drum set (known as drummers’ row) and sitting there checking me out were 3 of my drum heroes, including Billy Hart, Albert “Tootie” Heath, and Louis Hayes!!! I was completely shocked!! Then Clark asked each of them to sit in, and I got to sit right next to them and check out each of them and how they interpreted the music…….it was so inspiring!!!

One more experience I’d like to share was getting the call from the great pianist/composer Kenny Barron. He called to see if I was available for a 3-week tour in South Korea and Japan with him, bassist Ray Drummond and tenor saxophonist Michael Brecker!! It was one of the highlights of my career to have an opportunity to play with these amazing artists and very kind, encouraging and supportive human beings. It was another dream come true that I will never forget!!

How would you describe the New York jazz scene and your experience as a female drummer?

New York City has been and will always be the mecca for jazz. Musicians around the world are drawn to its palpable energy and the many opportunities to meet, perform and tour with some of the greatest musicians alive today. Every serious jazz musician should spend some time in NYC to study with their heroes/sheroes, listen to the jazz masters play live and feel the urgency in the air, which always seems to come out in the music. From the time I started playing the drums, it was something that I truly enjoyed. I wanted to learn and improve my playing so that I could have the experience of playing with musicians who were better than me. I challenged myself by working on my weaknesses so that I could expand my vocabulary and express myself better in my instrument.

I was aware that I was entering a male-dominated field, but I never thought about that very much. I just knew that I found something I loved to do. I never had time to think negatively about being a woman drummer on the NYC jazz scene. For me, it’s always been about the music and constantly striving to be a better musician. The music doesn’t have a gender. If you study your craft, put the work in and play with passion, the musicians who hear you will respect you, and you will get hired. Of course, there will always be those musicians who would never even consider hiring a woman. I stay away from them and instead surround myself with positive and open-minded people.

Photo provided by Sylvia Cuenca

Concerning releasing your own music, do you enjoy the composition process? What does this process look like for you?

I’m still developing as a composer, and I plan on spending more time growing in this area. I have many pages of fragmented ideas that I’d like to complete. I’m usually inspired by an incident in life, a memorable experience, or a musical idea that I’ve heard someone play. Sometimes, I’ll compose a tune based on a drum groove that I love to play, and I’ll try to layer ideas on top of it. On my first CD as a leader, I wrote a tune, and it’s the title track called The Crossing. It’s dedicated to a close friend and gifted pianist, Mercedes Rossy, who suddenly passed away as her career was taking off. It was shocking and heartbreaking to the entire NY jazz scene. I tried to convey some of these emotions in that composition. I’ve been a huge fan of Brazilian music for a very long time. On my new CD, I wrote a samba called Resiliencia, which means Resilience in Portuguese. I wrote it during the pandemic and dedicated it to all the musicians around the world and what we had to endure during the dark times of the pandemic. For me, it’s a gradual process, but I’m looking forward to continuing my journey as a composer.

As you have been performing with huge artists over the last 20 years, how has the scene changed? Do you think there is anything else that needs to change?

I moved to NYC from San Jose, CA, on August 22, 1985. At that time, there were all kinds of jazz clubs in NYC. Innovators of this music would be performing every night, and it was very common to see them hanging out after their gigs at late-night clubs like Bradley’s in the village. At that time, bands led by legendary musicians would hold frequent auditions for upcoming tours and performances.

There were opportunities for young musicians to be mentored by leaders like Art Blakey, Horace Silver, Betty Carter, Freddie Hubbard, Elvin Jones, Art Farmer, and Clifford Jordan, to name a few. The biggest difference between the scenes in the 1980s and now is that these kinds of mentoring opportunities do not exist anymore. This is mostly because a lot of these musicians have passed on and also because the group concept isn’t as prominent as it was back then. It’s unfortunate for young musicians of today because you can’t get this kind of playing or road experience from the classroom or a textbook.

Photo provided by Sylvia Cuenca

It would be great if there were more opportunities today to mentor younger musicians. I think by mentoring them there would be less arrogance and more humility and respect for older established artists. I think it’s still important for young musicians to study and know the rich history of this music and know the lineage of the players that helped to create it. For drums, the great drummer Lenny White refers to this list as The Magnificent 7. These are the drummers that helped to shape modern drumming as we know it today. They include Kenny Clarke, Art Blakey, Max Roach, Philly Joe Jones, Roy Haynes, Elvin Jones, and Tony Williams. Knowing the history gives your playing more depth and meaning.

What do the next steps look like for you? What will you be getting up to in the next few years?

Currently, I’m bi-coastal and splitting my time between the San Francisco Bay Area and New York City. I’m enjoying reconnecting with musicians I knew in California a long time ago and also connecting with new musicians on both coasts. I want to continue to grow as a musician and composer…. there’s always something new to learn. I’m also hoping to tour more with musicians and friends who inspire me to play my best. Right now, I’m also in the middle of mixing a recording from a few years ago. I’d like to complete this and release it sometime in the new year and have a CD release at a club in NYC.

This interview was originally published in the December 2024 Women in Jazz Media magazine

Last modified: January 14, 2025