Few episodes in jazz history are as loaded with irony and as emblematic of Cold War cultural conflict as the Jazz Ambassadors tours. In the late 1950s and 1960s, at the dawn of the American civil rights movement, the U.S. State Department launched a sweeping initiative to send leading American jazz musicians across the globe as representatives of American democracy.

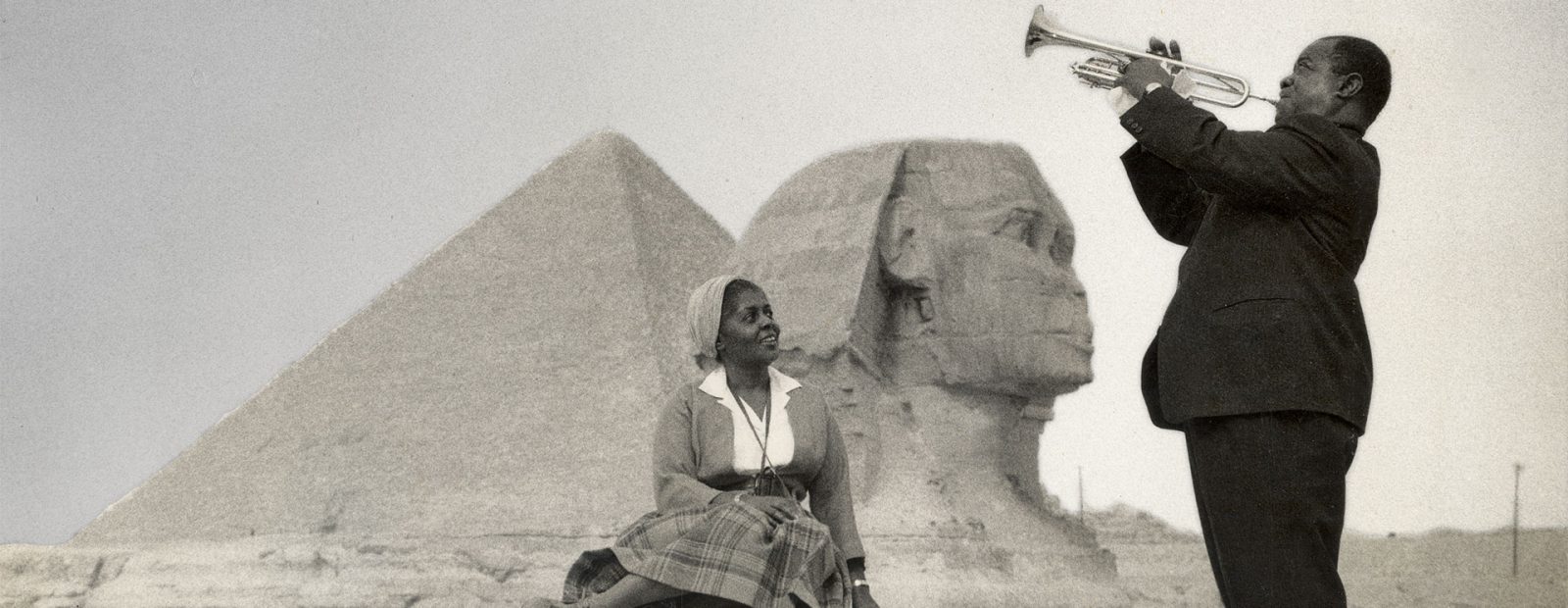

The official narrative was clear: jazz, a uniquely American art form shaped by African American artists, was to be showcased as proof of a vibrant, free, and integrated society. Yet, at the very moment Louis Armstrong, Dizzy Gillespie, Dave Brubeck, and Duke Ellington found themselves on international stages, Jim Crow segregation, racial violence, and deep systemic injustice persisted at home.

For much of the world, and for the musicians themselves, the U.S. government’s effort was blatantly hypocritical: propaganda promoting unity and equality, while the reality at home delivered daily contradiction.

he Jazz Ambassadors program was born out of geopolitical anxiety and “image management”, in other words propaganda. Facing fierce criticism from Communist rivals and a world watching the unfolding civil rights battles (Little Rock, Montgomery, Brown v. Board, etc) the Eisenhower administration turned to jazz as its most powerful cultural export. Black artists were hand-picked to represent a country still deeply segregated, with integrated bands paraded as living symbols of American progress.

These tours were intended to show the world that the U.S. was moving “rapidly towards full and equal citizenship” for all, especially African Americans. The State Department spotlighted jazz’s international appeal and improvisational freedom, yet foreign audiences, acutely aware of police violence, lynchings, and white resistance back in the States, were quick to note the disconnect. Propaganda films and pamphlets featuring smiling, successful Black musicians played out alongside news of Emmett Till’s murder and civil rights clashes, leading to skepticism and outright accusations of hypocrisy both abroad and at home.

These tours were intended to show the world that the U.S. was moving “rapidly towards full and equal citizenship” for all, especially African Americans. The State Department spotlighted jazz’s international appeal and improvisational freedom, yet foreign audiences, acutely aware of police violence, lynchings, and white resistance back in the States, were quick to note the disconnect. Propaganda films and pamphlets featuring smiling, successful Black musicians played out alongside news of Emmett Till’s murder and civil rights clashes, leading to skepticism and outright accusations of hypocrisy both abroad and at home.

Given the profound contradictions at play, many of the Jazz Ambassadors were initially reluctant participants in these State Department tours. Louis Armstrong was the most critical, at first refusing to go and famously declaring: “The way they’re treating my people in the South, the government can go to hell…”. Despite such strong reservations, he ultimately agreed, stating after visiting Africa, “I came from here, way back. At least my people did. Now I know this is my country too”.

For others like Dizzy Gillespie and Dave Brubeck, the decision was equally fraught; Gillespie joked, “We became the kamikaze band representing our country,” and pointed out, “I represent America. America consists of two things: White people and Black people. They send me out as a Negro, but I represent both”. Brubeck saw the tours as a chance to promote understanding, insisting on his band’s integrated lineup even when it met resistance at home, later reflecting, “We were reaching the artistic people and the students,” but used his musical “The Real Ambassadors” to expose “the absurdity of institutionalized political racism in the U.S.”.

It’s clear that the musicians believed the goals of cultural connection and honest dialogue outweighed the manipulative means. While some may argue that their participation helped shape America’s image abroad, history reveals their well-meant efforts were co-opted as propaganda tools in a narrative that glossed over racial injustice.

While the U.S. sent the Jazz Ambassadors abroad to project an image of racial harmony, at home a parallel, and at times defiant, story unfolded. Many prominent musicians directly confronted segregation, injustice, and the government itself by aligning their music and public actions with the civil rights movement. Charles Mingus is perhaps the most emblematic of this resistance tradition: an outspoken figure whose work, such as “Fables of Faubus,” ridiculed segregationists and used jazz as a pointed political weapon. Mingus publicly refused to sanitize his critiques, instead pushing boundaries on stage and in the studio, advocating for both musical and social liberation.

Max Roach stands alongside Mingus as a pivotal activist. His “We Insist! Freedom Now Suite,” with Abbey Lincoln, remains a landmark in protest music, directly referencing sit-ins and the call for equal rights. John Coltrane’s “Alabama,” Sonny Rollins’ “The Freedom Suite,” and Nina Simone’s “Mississippi Goddam” each forged urgent sonic connections with the movement, blending mourning, protest, and hope into the jazz idiom. These artists, among others like Archie Shepp, the Art Ensemble of Chicago, and Billy Taylor, made activism inseparable from their art. Their music’s open resistance gave voice to a marginalized America, inspired protest, and built solidarity, reaching listeners both inside and outside the movement.

Max Roach stands alongside Mingus as a pivotal activist. His “We Insist! Freedom Now Suite,” with Abbey Lincoln, remains a landmark in protest music, directly referencing sit-ins and the call for equal rights. John Coltrane’s “Alabama,” Sonny Rollins’ “The Freedom Suite,” and Nina Simone’s “Mississippi Goddam” each forged urgent sonic connections with the movement, blending mourning, protest, and hope into the jazz idiom. These artists, among others like Archie Shepp, the Art Ensemble of Chicago, and Billy Taylor, made activism inseparable from their art. Their music’s open resistance gave voice to a marginalized America, inspired protest, and built solidarity, reaching listeners both inside and outside the movement.

The effects of their resistance were profound. By refusing silence on the bandstand, in lyrics, and in leadership, these musicians inspired activism, raised consciousness, and extended the possibilities of jazz as a vehicle for social change. Their efforts not only reflected Black America’s struggle for justice but also challenged audiences (Black and white, domestic and foreign) to recognize the gravity of the struggle. This willingness to use jazz as direct, often risky, protest powerfully contrasted with the government’s attempts to package the music as harmonious narrative. The movement’s soundtracks, songs of sorrow, hope and defiance, echoed globally, as did the story that the struggle for dignity and freedom was unfinished.

This dual role of jazz (state-sponsored symbol abroad, resistance anthem at home) set the stage for the music’s fraught reception and transformative power behind the Iron Curtain, where jazz became both a voice of aspiration and a cipher for cultural resistance.

Behind the Iron Curtain, jazz flourished in unexpectedly vibrant and innovative ways, particularly in countries like Poland, Czechoslovakia, and East Germany. Despite official suspicion and intermittent censorship, tightly controlled regimes inadvertently fostered underground scenes where musicians experimented freely, pushing the boundaries of the art form. In Poland especially, jazz became a powerful cultural statement, blending technical virtuosity with avant-garde experimentation that, in some ways, surpassed developments in the West. The decade-long “catacomb jazz” era saw musicians playing in private apartments and hidden venues, driven by passion and a desire for creative freedom despite the risks.

In Poland, early Cold War repression declared jazz a decadent Western influence, severely limiting public performances and access to records, leading to a blackout of legitimate jazz education and promotion. Yet, young Polish artists covertly sustained the music, creating a rich underground culture through groups like the Melomani, a collective of avant-garde musicians who folded jazz’s improvisational spirit into their own experimental language. The scarcity of official resources forced Polish jazz to innovate in response, nurturing complex, idiosyncratic styles that remain influential today.

Similarly, in Czechoslovakia, jazz survived through a delicate balance of official tolerance and underground resistance. The vibrant Prague Jazz Section became a nucleus for independent artistry, blending modern jazz idioms with local traditions, often serving as a form of cultural dissent against Communist authority. East Germany’s jazz culture was marked by official preference for conservative styles like Dixieland but also featured a thriving clandestine scene. Secret underground sessions, and cautious collaborations flourished despite surveillance, illustrating the music’s resilience as a voice of nonconformity and cultural emancipation.

These underground and semi-official scenes behind the Iron Curtain not only preserved jazz but expanded its expressive potential in politically charged contexts. They laid the groundwork for dynamic exchanges with Western musicians, shaping jazz diplomacy’s later phases and revealing jazz’s profound role as both art and political symbol in Cold War Europe. This multi-layered backdrop sets the stage for understanding the complex interactions of culture, politics, and music that characterized the era’s jazz diplomacy.

Both the Eastern Bloc and the United States experienced politically charged jazz scenes shaped by forms of oppression but with distinct contexts and expressions. Behind the Iron Curtain, jazz was often underground and subversive, nurtured in secret venues and private apartments under the watchful eyes of authoritarian regimes. Musicians responded to censorship and ideological constraints by pushing the boundaries of creativity, cultivating idiosyncratic and avant-garde styles that became subtle acts of cultural resistance. Their music was a coded language of freedom and defiance, endured in a climate where open dissent was dangerous.

In both environments, oppression did not silence jazz; it galvanized musicians toward a politically potent art form. These parallel scenes demonstrate how jazz uniquely served as a voice for the marginalized, whether hidden from a repressive state or shouting into the public square demanding civil rights. The creativity born from constraint reveals the genre’s enduring power as both cultural expression and political resistance.

The Cold War jazz diplomacy program was an audacious contradiction at its core. While the U.S. government sent jazz musicians around the world to tout American racial progress and democratic ideals, at home those same musicians and their communities were locked in a fierce struggle against systemic racism and segregation. The official narrative was propaganda, a carefully crafted story masking deep inequalities and social injustice. Yet, ironically, it was these very musicians who, through their art and activism, exposed those contradictions, inspiring change both domestically and internationally.

Meanwhile, behind the Iron Curtain, jazz resonated as a clandestine form of cultural resistance against authoritarianism, often more openly subversive and politically charged than the sanitized tours sponsored by the State Department. In both East and West, jazz became a battleground where music articulated struggle, resilience, and the demand for freedom. This paradox—jazz as both a tool of state image-making and a weapon of protest, illuminates the complexities of Cold War cultural diplomacy. It underscores how, despite political agendas, jazz remained a profound expression of human aspiration and defiance, shaping narratives far beyond what any government could control.

Last modified: September 30, 2025