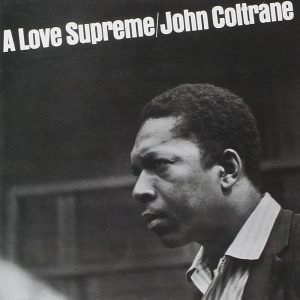

Editors Note: For the 65th anniversary of John Coltrane’s iconic album A Love Supreme, I, asked Michael Binder to reflect on the enduring legacy and significance of this iconic album This milestone offers a unique opportunity not only to revisit the history of this groundbreaking work, but also to consider its continued influence on music, culture, and spirituality six and a half decades after its release.

When Andrew [Read] asked me to write an article about John Coltrane’s iconic 1964/65 album A Love Supreme, my first thought was: When was the last time I truly listened to this masterpiece?

When Andrew [Read] asked me to write an article about John Coltrane’s iconic 1964/65 album A Love Supreme, my first thought was: When was the last time I truly listened to this masterpiece?

With 2025 marking the 65th anniversary of its release in 1965, I realized this milestone offers more than a chance to revisit the album’s history and significance—it invites us to explore what it means to experience A Love Supreme today, six decades later. How has this transcendent work continued to shape music, culture, and spirituality? What has changed over the years because of it?

This anniversary is the perfect opportunity for a deep dive—not only into the album’s creation and the exceptional musicians who brought it to life but also into its enduring impact. Listening to A Love Supreme in 2025 is not just about nostalgia; it’s a reflection on its spiritual and cultural resonance in our time.

More than just music, A Love Supreme was Coltrane’s prayer, his declaration of faith, and a groundbreaking jazz suite that broke the boundaries of the genre. Created in an era of civil rights struggles and profound personal transformation, the album offered a work of unparalleled spiritual depth. It remains a testament to the power of art to inspire, uplift, and transcend the moment of its creation.

Acknowledgement

This album was truly revolutionary for its time. But after 65 years, with so much music created in the interim, it might feel antiquated to some. And here’s an interesting question: if it’s so iconic, why aren’t there more reinterpretations of it?

First, it’s still a challenging listen, even today. However, after decades of experimenting with different aesthetic approaches in music and art, A Love Supreme feels like a foundational starting point for much of what followed. If we think of Miles Davis’s Kind of Blue as taking one path, A Love Supreme might represent the other—perhaps asking to the contrast between Debussy’s impressionism and Schoenberg’s expressionism at the beginning of the 20th century and to truly appreciate its signifcance, it’s essential to consider the broader cultural and artistic landscape of the 1960s.

Resolution

Let’s take a moment to look back at the events of December 9th and 10th, 1964—the two days when A Love Supreme was brought to life. There are several key aspects I’d like to highlight, but for those who want to delve deeper into the history and significance of this monumental work, I highly recommend Ashley Kahn’s book, A Love Supreme. It’s an essential resource for anyone seeking a comprehensive exploration of this masterpiece.

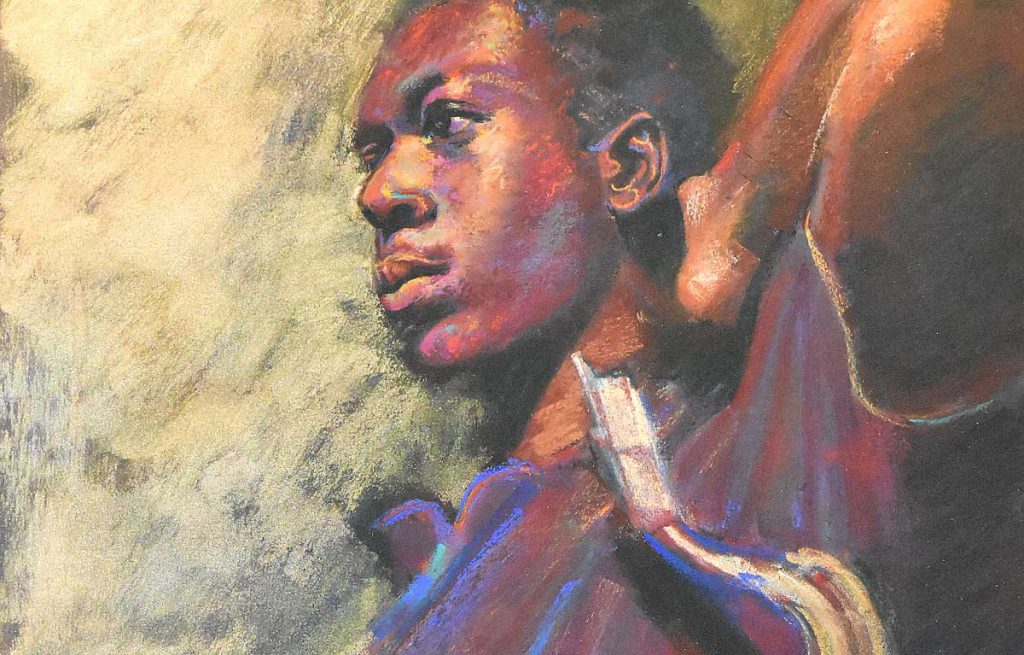

One important point to emphasize is that A Love Supreme is not simply the product of four genius musicians working in isolation—it’s the culmination of years of collaboration, growth, and shared experience. The “Classic Quartet,” as they are now known, was formed by John Coltrane in early 1962. Comprising McCoy Tyner on piano, Jimmy Garrison on bass, and Elvin Jones on drums, this ensemble can be seen as the jazz equivalent of a classical string quartet: a tightly knit group capable of incredible depth and synergy.

Their first studio album together, Coltrane (1962), already showcased the immense ability and potential of this group. But it would take over two years of intensive work—including countless performances and recordings—for the quartet to fully realize their possibilities. Along the way, they played with legendary artists like Duke Ellington and recorded landmark sessions, such as the so-called “lost album” Both Directions at Once in 1963.

If we borrow the phrase “Nothing comes from nothing, nothing ever did” from The Sound of Music, we begin to understand the incredible journey that led to A Love Supreme. For example, hearing Coltrane’s rendition of My Favorite Things—performed with Wes Montgomery on guitar—offers a glimpse into the relentless experimentation, refinement, and artistry that made a masterpiece like A Love Supreme possible.

Drummer Elvin Jones once shared that “they had played the music [A Love Supreme] already before the recording in different clubs.” He added, “The musicians didn’t know what would happen, but they sensed what they might have to do.” This insight highlights an essential point—it’s almost impossible to record an album of this depth and complexity in one session without having some familiarity with the material. Especially when Coltrane himself gave very few instructions, the musicians had to rely heavily on their intuition and connection as a group.

This level of sensitivity and trust among the musicians could only come from having played together extensively, night after night, in countless gigs. It’s worth emphasizing that this doesn’t take anything away from the groundbreaking nature of the album. Instead, it underscores an important truth: exceptional achievements often require exceptional preparation. The familiarity and shared understanding among the players allowed their creativity, spirit, and musicality to flow freely when it truly mattered.

What happened on December 9, 1964, was remarkable for this reason, and the events of the next day add another fascinating layer to the story. As Ashley Kahn noted, the mystery surrounding this recording session—where Coltrane invited musicians like Archie Shepp on tenor saxophone and Art Davis on second bass—only adds to its legendary status. The lost master tapes from this session further amplify its mystique. I found a recording of Acknowledgement from this session on YouTube, but most of what we know comes from the accounts of the musicians involved, which Kahn explores in detail in a dedicated chapter of his book.

During this session, much like with the classic quartet recording, Coltrane gave only verbal instructions to Shepp and Davis—no written music. Davis recalls being told “to play in the higher registers” while Jimmy Garrison focused on the lower lines. Davis also mentions using the bow during parts of the session, but when the time came to record, they simply started playing.

What emerges from this session, in my view, is a fascinating extension of the original quartet version—a musical expansion rather than a reinvention. One particularly striking element is the interplay between the two tenor saxophonists, Coltrane and Shepp. You can hear two distinct voices, two personalities shining through the same instrument. This individuality in sound feels rare today, especially in classical music, though perhaps less so in jazz.

Analogue Productions is offering this masterpiece in UHQR format on Clarity Vinyl, housed in a deluxe box. Expertly mastered and cut by Ryan K. Smith at Sterling Sound, the release offers exceptional transparency and clarity. The set is pressed at 45 RPM to provide the best possible listening experience. The double LP is limited to 10,000 copies and includes a 12-page booklet featuring liner notes by acclaimed music editor Ashley Kahn and photos from the Coltrane house.

At the end of the track, there’s a duet/solo featuring the two bassists. One (likely Garrison) plays the A Love Supreme motif, while the other (Davis) solos over it. However, Davis’s arco playing is subtle and almost inaudible in the mix. Before the concluding pizzicato duet, there’s a faint suggestion of arco bass in the background, but it’s not distinctly audible.

What we’re actually listening to here is an entirely new piece. This concept of “two double basses,” as Art Davis described it, resurfaces in Ornette Coleman’s 2005 recording Sound Grammar, where the interplay of Tony Falanga’s arco bass and Georgy Cohen providing harmonic foundation creates a similarly layered texture.

Pursuance

What really stands out about this album is that it’s structured as a single piece—a suite of four distinct movements. That’s a bold statement, especially considering the norm at the time, which leaned heavily on collections of tunes, songs, or standards rather than cohesive, extended works. The four movements, intriguingly titled Acknowledgement, Resolution, Pursuance, and Psalm, break away from convention entirely. These titles hint at the unity of the work as a singular piece and open up a wider space for musical creativity, improvisation, and evolution.

Another fascinating aspect is the title itself, A Love Supreme. It’s not just the name of the album but also an integral part of the music. It’s introduced in a unique way at the end of Acknowledgement, where Coltrane starts vocalizing the main four-note motif, originally played by the bass after the brief introduction. With those words, the album’s title becomes woven directly into the fabric of the music.

There’s also an intriguing connection between the micro and macro form here. The four-note motif not only serves as a central musical idea but might also re?ect the structure of the entire suite’s four movements. This interplay of thematic unity and larger structural cohesion is a key part of what makes the album so innovative.

So, what are we hearing 65 years after its release? I hear innovation born out of simplicity. Or, more precisely, simplicity as the bedrock for complexity, and complexity as a means of human expression. For example, the opening of Acknowledgement evokes echoes of Debussy’s La Mer—the resonant gong and the saxophone’s brief, exploratory motifs feel strikingly similar in their atmosphere. But maybe “simplicity” isn’t quite the right word. “Limitations” might be more accurate.

What emerged in those December sessions was revolutionary. The quartet created a suite built around a simple four-note motif that transformed through multiple keys while maintaining its spiritual center. Jones’s polyrhythmic drumming provided the anchor, while Tyner’s innovative quartal harmony opened new spaces for Coltrane’s explorations.

The four-note bass ostinato, mantra-like in its repetition, becomes a foundation for rhetorical, musical questioning as it shifts through various keys. Then, just when you think you understand the pattern, Coltrane surprises us with the vocalized mantra of A Love Supreme. This constrained harmonic, rhythmic, and melodic palette allows for the creation of something truly monumental—a complex, cathedral-like sound that feels both intimate and expansive.

What stands out most, however, is the almost symbiotic connection between the quartet members. This isn’t just about Coltrane’s saxophone; it’s about the interplay beneath: McCoy Tyner’s piano, Jimmy Garrison’s bass, and Jones’s drums working as a unifed whole. The musical understanding between them is palpable.

A suite, in its classical sense, is a series of interconnected dance pieces. Could Coltrane have been inviting us to dance? Perhaps. But the suite’s structure also reveals a clear adherence to the “Golden Ratio,” with the peak of complexity occurring about three-quarters of the way through, in Pursuance. The ?nal movement, Psalm, serves as a natural release of tension, a moment of serene resolution after the dramatic climax. This structural balance—building tension and releasing it—is a fundamental aesthetic principle in nearly all Western art forms, and it’s masterfully realized here.

Psalm

The real question here is: what’s it like to listen to A Love Supreme again after so many years? How is Coltrane’s musical legacy being treated today? Does it still hold signi?cance or relevance in a world that’s heard so much music since its release?

To explore this, I’ve picked three contemporary interpretations of A Love Supreme. While I’ve also listened to versions by Alice and Ravi Coltrane, I’ve chosen musicians who, let’s say, aren’t directly connected to the Coltrane family.

One of the first things I noticed when listening to modern takes is how the saxophone tone has changed. In the original recording, Coltrane’s playing is undeniably expressive but never harsh or overly aggressive. There’s always this warm, mellow layer in his sound, no matter how intense the music gets. By contrast, many contemporary versions feature a much more “punchy” tone.

The frst interpretation I chose is by the Branford Marsalis Quartet. For me, it’s like they’ve taken the core musical ideas of the original and brought them into a contemporary setting. The instrumentation mirrors the original quartet, but the perspective is distinctly modern. This version re?ects what A Love Supreme means to musicians who come from very di?erent musical and cultural backgrounds than Coltrane’s in the 1960s.

Next is Wynton Marsalis’s orchestration of A Love Supreme for the Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra. Here, you can really see how simplicity can lead to complexity in a different way. The complexity isn’t in the improvisation or raw interplay of a quartet—it’s in the creation of a symphonic, layered soundscape out of what was originally an intimate session between four musicians. The overall tone is lush and mellow, reminiscent of the big band era, yet it offers a fresh perspective on this classic work.

The last interpretation is by the young saxophonist Lakecia Benjamin. She focuses on just two movements, Acknowledgement and Pursuance, in her 2020 album The Coltranes, which also features music by both Alice and John Coltrane. Benjamin’s approach feels the most personal of the three. Rather than a full reinterpretation, she extracts key elements from Acknowledgement and reimagines them in a shorter, more modern, and intensely emotional version. With Dee Dee Bridgewater’s powerful voice, Benjamin brings a contemporary edge that redefines what A Love Supreme means to her.

A Love Supreme as Conclusion

These reinterpretations highlight an intriguing phenomenon: what gets lost over time, even when we have a sonic testament of the original. They reveal what’s considered significant now versus what it might have meant back in the 1960s or 70s. There’s something intangible, a kind of “patina,” that builds up over the years—layers of interpretation, context, and emotion that settle over a piece of art as time passes. By the end, we’re no longer hearing the original Coltrane, Beethoven, or Bach.

Music is ephemeral, fluid; the moment you hear it, it’s already gone. But in its fleeting nature lies its power—a brief glimpse of what it means to be fully present. In A Love Supreme, Coltrane and his legendary quartet captured that glimpse for a moment, and we’re lucky to have it preserved.

For those unaccustomed to complex music, this album can feel overwhelming. Even now, after all these years, it remains a dense, intricate work. You might need time to settle into its rhythms and ?nd your bearings amidst the whirlwind of ideas. But once you do, the complexity reveals itself as a lush, living organism—a labyrinth of interconnected musical growth and expression.

As we celebrate the 65th anniversary of A Love Supreme, I find myself reflecting on its enduring lessons: perseverance, gratitude, and spiritual discovery. If you haven’t listened to it recently—or ever—now is the perfect time to immerse yourself in its transcendent beauty.

Last modified: June 27, 2025