Kicking off a new series by Marieke Meischke titled “Cities of Jazz, Marieke travels to Budapest to speak with two of the cities top exponents of the jazz scene, vocalist Veronika Harcsa and guitarist Bálint Gyémánt. This is the first in a series of features where Marieke explores a cities jazz scene through the eyes of the musicians that inhabit it. Stay tuned for the next stop on Marieke’s tour.

Budapest, the capital of Hungary, is a city steeped in rich musical history, being the birthplace of renowned composers such as Franz Liszt, Ern? Dohnányi, Zoltán Kodály, and Béla Bartók. Yet, beneath its classical legacy lies a vibrant and evolving jazz scene that remains largely undiscovered by many. In this interview, I delve into the world of jazz in Budapest through the insights of two prominent local musicians: vocalist and composer Veronika Harcsa, and guitarist and composer Bálint Gyémánt.

Both artists have been instrumental in shaping the contemporary jazz landscape in Hungary, drawing from their diverse backgrounds and experiences. Our conversation reveals not only their personal journeys into the realm of jazz but also the broader context of the music scene in Budapest. They discuss the challenges and triumphs of being musicians in a city that is increasingly becoming a melting pot of cultural influences, where traditional sounds meet modern experimentation.

Marieke Meischke: Were you both born in Budapest? If so, How should I refer to you?

Veronika Harcsa: Budapesters, haha. Yes, we are from Budapest.

MM: I would like to ask you some personal questions first, if I may. Do you remember the first time you were struck by jazz? I assume you were exposed to classical music first.

VH: I come from a family where there wasn’t too much music around. My parents had friends who were classical musicians, and we would go to their concerts when I was a kid. My parents encouraged me to take piano lessons since their families couldn’t afford to give that to their children. I enjoyed making music, but as a teenager, I wanted to do something else, something more hip, so I chose the saxophone just because it looked cool. At my first lesson, my teacher asked me if I wanted to play classical music or jazz, and I didn’t know anything about jazz, but it sounded cooler, so I immediately wanted to study jazz.

MM: So, you couldn’t choose pop music?

VH: No, it was either classical or jazz. It was love at first sight with jazz. I was fifteen, and from then on, I went to concerts and listened to records. It just blew me away—the freedom. Through my teacher, I was mainly exposed to American jazz, but I did listen to other music. The community I grew up in, near Budapest, was a mix of Swabians of Southern German descent and people with Serbian roots who have been here for centuries. There were amazing bands playing Serbian traditional music and some Swabian music, which was not that interesting to me. But the Serbs… don’t think of wedding bands. They were classically educated musicians playing the most beautiful songs. And then there was Hungarian folk music too, so all this came together.

MM: And at some point, you switched from the saxophone to singing?

VH: Yes, my parents bought me a CD of Toots Thielemans. It was an album of Gershwin compositions, and international stars sang the songs, like Sting, Rod Stewart, and Lisa Stansfield. That was something that was easy for me to connect with, so I wanted to try this as well. At music school, I sang “Summertime” and “It Ain’t Necessarily So.”

MM: So you were very attracted to compositions with strong melodies?

VH: Yes, and I liked the lyrics and the performance aspect. It felt like I could express more with my voice than with the saxophone.

MM: How did the two of you find each other?

Bálint Gyémánt: We met at the academy of music (Liszt Academy of Music, as it is called in Hungary) exactly 20 years ago.

VH: We were in the same class in our early twenties.

MM: Bálint, where do you come from?

BG: I am also the first professional musician in my family, but my grandfather was a very good amateur accordion player, and at every family gathering, he would play his instrument. My father is a great music lover; he had hundreds of vinyl records, mostly rock music and a lot of jazz guitar. My mother sang in the radio choir when she was young, which was quite a big deal in communist times. At the age of 12 or 13, I started to play classical guitar. I loved it, and I was super lucky with my teachers. Just two half-hour sessions a week at the local music school provided a touch of music in a child’s life, but for me, it meant a lot.

It soon became clear that I needed more freedom in my playing than I could find in classical music. I was always moving a lot when I played, and I was supposed to be calmer while performing. But my teacher was so nice; after four years, she said she would find the best jazz teacher for me. She was very generous and found someone for me. For four more years, I studied classical guitar simultaneously. The instrument was a big inspiration for me. The first CD I owned was one by Eric Clapton, where he didn’t play original compositions but blues standards, like “Hoochie Coochie Man” (album “From The Cradle” – 1994). My teacher introduced me to Wes Montgomery, John Scofield, and Pat Metheny—the obvious names in those days.

MM: So then comes the moment when you decide to study music and become a professional musician. Were there places in Budapest where you could go to hear live music that appealed to you?

VH: Now we have the Opus Jazz Club, Budapest Jazz Club, and Budapest Jazz Center. But they weren’t there in those days. We went to Long Jazz Club and Jazz Garden, and then there was a big boom around 2007-2008 when two new jazz clubs opened within a year: Budapest Jazz Club and Take Five. We could really feel that boom, and Bálint and I are of the generation that was ready to join it. We were at the right place at the right time. We had the right age and released our first albums; it was perfect timing for us.

BG: It was our diploma year. I remember in the first semester, I was in Oslo (Bálint was the first Hungarian student to be awarded a scholarship to the Academy of Music there). We had Skype, and my friends would be really excited online, saying, “You won’t believe it! We have two new jazz clubs opening!” It really was something!

VH: Yes, and in the same year, a national radio station, Pet?fi Rádió, renewed its programming. They started to develop a really brave taste, broadcasting a lot of Hungarian alternative music, and some jazz players fit in, especially the more groovy ones. Now the station has unfortunately reverted to mainstream programming, but those days left a mark. Opus Jazz Club and the Budapest Music Center (BMC) opened, which is an incredible place. I have a very strong collaboration with them, and if it weren’t for them and Opus, I wouldn’t be here like this. They contribute so much to the scene and to Hungarian musicians, both jazz and contemporary classical music.

BG: Yes, it is really unbelievable what they are doing.

MM: I know BMC mainly as a record label, ECM-like, but it is much more than that, isn’t it?

VH: There are similarities, but to us local Budapest-based musicians, the center is a place where we go to rehearse and record in their studio. For BMC artists, they always find a way to fund video shoots or concert recordings. They have guest rooms for musicians from abroad, a music library, and a restaurant.

BG: Yes, everything is there. I did an album featuring Shai Maestro, and they took care of everything for us—the studio, catering, and accommodation. They are wonderful, music-loving people who run the place.

MM: Veronika, what is the flow of your musical career?

VH: I founded a jazz quartet in 2005 and released four albums, two of which reached the top of the vocal jazz charts at Tower Records in Japan. I was also involved in the alternative music scene in Hungary, collaborating with the Erik Sumo Band, the Pannonia Allstars Ska Orchestra, experimental electronic trio Bin-Jip, and avant-garde poet Lajos Kassák. It has been quite a versatile journey. At some point, though, I wanted to expand my horizons and went to the Royal Conservatory of Brussels to pursue a master’s degree, to discover new ways of singing and study new vocal techniques.

VH: After Brussels, I lived in Berlin, and then I met my husband, and we moved to London. In total, I spent seven years flying back and forth, always staying in touch with the Hungarian scene and developing strong connections with the Belgian and German scenes. Four years ago, we moved back. We were hoping to have a child and figured that flying back and forth between our homes was not the best way to conceive, so we decided to settle in Budapest. We had our first child in July.

MM: Congratulations! Have you found a balance now? Living, recording and performing in Hungary and abroad?

VH: Yes, Belgium and Germany have become very important, but I am strongly connected to the Hungarian scene, and it is amazing; I love it. I have wonderful opportunities and collaborations; my main projects can be developed here. It is always nice to try out things here that I can later take abroad.

MM: Would you describe the vibe as very open and curious, with a lot of space for new things and experiments?

VH: Absolutely. There is a lot of space for experimental things in Budapest; of course, it’s a niche, but there is an audience for it. There is support; we can apply for funding for projects, working together with BMC. That said, most musicians are struggling to make ends meet. Bálint and I are two of the lucky few who can buy a place and live a proper life as musicians. But I see a lot of people around me who have to teach, not out of love for teaching, but out of necessity. Or they are doing something else on the side.

MM: Bálint, when we spoke earlier, you mentioned doing a PhD, so the pay will be better when you teach.

BG: That is the master plan. But I am also super lucky; I love to teach. It is a very important part of my musical life. It is a privilege to live as a musician and play the music that you love with people that you like. As a musician there are possibilities, but especially as a jazz musician—someone more experimental—it is fantastic to be in the position we are in, especially in Hungary.

VH: But if we talk about the scene itself, not about the financial side, if you have creative ideas, you will definitely find partners for them in Hungary. Because there really is a scene that is very open-minded. Now we are starting to see generations, including ourselves, that studied abroad and came back. Budapest is becoming more international; not like in Western Europe, but more and more musicians have connections with those from abroad. We talked about the two clubs, which are real jazz clubs in the best sense of the word, but you’ll find other smaller venues programming jazz. They may pay the musicians a lower fee, but some of them, like Jedermann Café, have a really nice selection, very good taste, and interesting niche projects. There is also a series for improvised music in a place called Jazzaj. You can hear free jazz there, and that has been going on for ten years now, I think.

MM: I dove into Hungarian jazz and have this big list of band names, also from the BMC ‘family,’ of course—very hard to pronounce. I have been around in the international jazz scene for about 30 years, and I am ashamed to say that there are not so many names I know. But they are well-known… yet not playing outside Hungary a lot?

VH: It is very hard to get out there. I have a personal theory. I think it is very much related to our unique language. We have no relatives. Nobody understands Hungarian, and the Hungarians don’t understand the others. Now the situation is getting better because Hungarians are starting to speak English, finally. But nobody understands us. I mean, Germany, Austria, and Switzerland are German-speaking countries, and there is Belgium, struggling to connect with France while at least sharing a language. The Flemish and the Dutch can communicate. Historically, there is a big community of Hungarians in Romania, and there we can tour because they understand us. But outside that…

MM: It’s a twilight zone between East and West. You can’t figure out where you belong. Is it like that?

VH: I think so, because we are not the Balkans; we are not the Slavic countries either. There is a historical connection with Austria, but, pardon me, I think they look down on us a bit.

BG: Absolutely.

VH: Everybody likes to look at the West.

MM: In jazz music, you tend to play classical instruments like the violin or accordion.

VH: Especially in the eighties, bands like that would tour a lot, combining traditional Hungarian folk music with jazz, like Mihály Dresch. But the generation of today is not so interested in this traditional Hungarian music anymore, so it cannot be sold as world music infused with jazz. If they played Western music, why would they invite a band from the East to play somewhere when they can find them in the West? So it is complicated. For example, looking at your list, there is the Nagy Emma Quintet. She is young, not yet 30, and the whole quintet consists of five geniuses. You should definitely listen to them.

MM: And there are hardly any women on that list. Are there women studying instruments at your music conservatory, or are there only singers?

BG: Mostly singers, for sure.

MM: Do, for instance, Americans come to play in Budapest? Which international artists are popular?

VH: There is a clear division. There is Opus Jazz Club and everywhere else. Opus really focuses on the European scene. You rarely find American bands there. They program European bands that are not known in Hungary but have found an audience there. It’s working very well. Then there are some festivals and the Budapest Jazz Club inviting foreign bands, which are 99% American, mostly the big names—no risk. Like John Scofield. The audience is not that jazz-loving, so if you want a full house, you need a name. Opus is the only place where you can discover new jazz artists.

MM: Are there some interesting young talents? Is it happening in Budapest at the academy or outside? Something new, super creative, like in Belgium, for instance?

BG: I’m not so sure. There are a lot of super talented musicians. The question is… are they ambitious enough and smart enough to take their music to the next level? I’m not totally sure about that. In Hungary, there are some super big pop names playing for 3 x 80,000 people, and the music business is sucking these talented musicians up. They want to make some money.

VH: They play bass or drums, are on the road all summer, and make money.

BG: Yes, at the Academy of Music, there are some really good players. It is my second year teaching there, so perhaps I don’t have enough experience yet to express my opinion. But I see that at the music conservatory—not the university—the talent is strong, and many of them go abroad to continue their studies. They go to Basel, Amsterdam, America, and I’m afraid that we are losing the very best ones. They realize that it is very hard to make a living as a musician or as a teacher in Hungary. So even being a music teacher abroad is much safer than being one in Hungary. Between the ages of 16 and 22, there are many talented musicians, but 90% are leaving the country. Hopefully, they will come back; God only knows. They have financial reasons, and there is politics.

MM: Well, don’t come to the Netherlands then… our elections were won by a guy who calls culture a ‘left-wing hobby.’ But let’s end on a positive note. Do you have any final words about jazz in the beautiful city of Budapest?

VH: Yes, I would like to encourage people to come and check it out. I think it is really worth it. We know it is very, very hard for Hungarian musicians to tour abroad; most of them remain unrecognized. So if you want to get to know them, it’s worth spending a week here and finding them. There is a concert every night for music lovers.

MM: For connoisseurs.

VH: Really.

BG: Super easy to do that here. My last words would be that we need a much better agency for Hungarian jazz musicians to improve their image. That would be nice.

VH: There is an export office, but they don’t really export; they support pop bands, not jazz. They don’t support touring, mostly showcases. It’s a bit limited. So, come to Budapest for a week and hear a great concert every night!

Photos by: Edina Csoboth, Glodi Balazs, Artur Ekler & Eszter Fruzsina

![]()

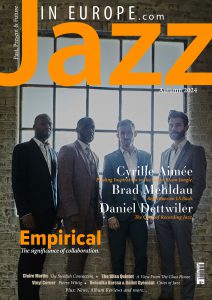

This article is featured in the Autumn 2024 edition of the Jazz In Europe Magazine. This edition features in-depth interviews with notable artists such as UK band Empirical and Brad Mehldau. Readers will find insightful pieces on the craft of recording jazz with Daniel Dettwiler, and explorations of the jazz scenes in Budapest and Sweden through conversations with artists like Veronika Harcsa, Bálint Gyémánt, and Claire Martin.

This article is featured in the Autumn 2024 edition of the Jazz In Europe Magazine. This edition features in-depth interviews with notable artists such as UK band Empirical and Brad Mehldau. Readers will find insightful pieces on the craft of recording jazz with Daniel Dettwiler, and explorations of the jazz scenes in Budapest and Sweden through conversations with artists like Veronika Harcsa, Bálint Gyémánt, and Claire Martin.

The magazine also includes a special “Vinyl Corner” segment featuring Pierre Wittig, an audio technician specializing in high-quality amplifier restoration. Additionally, readers can enjoy album reviews, a thoughtful editorial on jazz’s response to corporate consolidation in the music industry, and a feature on Cyrille Aimée and finding musical inspiration in Costa Rica.

Last modified: November 19, 2024