We’re excited to present the second instalment of our in-depth conversation with Daniel Dettwiler, a renowned European recording engineer celebrated for his expertise in jazz. If you haven’t already, we strongly recommend revisiting Part 1 of this interview, where we explored numerous aspects of recording jazz. You can find this first part of the interview here.

In this continuation, we’ll delve into several crucial topics, including techniques for maintaining dynamic range, the ongoing debate between analogue and digital technologies, and a wealth of additional insights from Dettwiler’s extensive experience. This segment promises to offer more valuable knowledge for both audio enthusiasts and professionals alike, further illuminating the intricacies of capturing the essence of jazz in the studio. So, let’s get back into it.

AR: When researching for this interview I saw a video where you explained the importance of dynamic range in a mix and capturing harmonics during tracking. You mentioned that over-compression can reduce upper dynamics and close down the overall dynamic range. This is a complex topic, but it’s crucial for good sound. Could you explain this concept in a way that non-recording engineers can understand? Why is preserving dynamic range and harmonics so important in the recording process?

DD: It’s indeed important, and I’ll try to explain it in simpler terms. Most musicians understand what harmonics are, so let’s start there. When you play a tone on an instrument, like a violin or piano, you’re not just producing one frequency. Let’s say you play a 100 Hz tone. You’re actually producing that fundamental frequency plus a series of harmonics at 200 Hz, 300 Hz, 400 Hz, and so on. These harmonics are crucial for how we perceive pitch and the instrument’s unique sound.

The higher harmonics are typically softer than the fundamental frequency. A musician’s ability to control these upper harmonics, often unconsciously, contributes to their “nice sound.” In a concert setting, skilled musicians adapt their playing to ensure all these harmonics are audible.

Daniel at the Critical Listening position in his studio.. He relies on Strauss SE-MF2 monitors for accurate mixing and mastering.

Now, here’s where recording and playback come in. When we record music and play it back through speakers, we’re giving volume control to the listeners. This is different from a live concert. If someone listens at a much lower volume than the original performance, those softer upper harmonics might become inaudible. As engineers, our job is to preserve these harmonics so they’re still present even at low listening volumes.

Many studios make the mistake of only checking mixes at loud volumes. But we need to ensure all those harmonics are audible even at soft volumes. Simply using compression isn’t ideal because it can make the sound, well, compressed.

This is where equipment like tube gear comes in. Tube equipment creates harmonic distortion, which essentially boosts existing harmonics and even creates new ones. Similar effects occur with tape and analog mixing boards. In the past, each step of the recording process would slightly boost these harmonics, making them more present in the final mix.

By using these techniques, we can ensure that even at low volumes, all the harmonic content is there. Then, we only need to apply a little compression at the end to get it in the final dynamic range. This approach helps preserve the natural sound and dynamics of the original performance while ensuring it translates well to various listening environments and volumes.

AR: I wanted to speak to you about your views on the difference between analog and digital. But before we dive into that, perhaps we can talk about the use of tube microphones, particularly vintage mics. You touched on this earlier. Could you elaborate on the types of microphones you prefer to use when recording?

DD: Well, the microphones produced in the 1950s, like the Neumann U47 or M49, are among the best. Interestingly, the technicians back then didn’t think these microphones were good because of their noise floor and harmonic distortion. They were hoping for more linear microphones with the invention of transistors. But ironically, the tube electronics were perfect for ensuring harmonics are present at lower volumes, which is crucial for modern recording.

It’s a bit of a lucky accident in history. The tube was never created to sound good, but it just does.

AR: I know you have quite a collection of vintage mics. How did you come to realize the value of using vintage mics and when did you start collecting them?

DD: I actually realized it quite late. When I was around 20 and studying, we had an analog console and tape machine, but our teachers were dismissive of this “old” technology, promoting digital techniques instead. I didn’t pay much attention to these “dinosaurs” at first.

It wasn’t until about 10 years into my career, after mixing digitally, that I felt something was missing – that last 10% in quality. I had a chance to record at Abbey Road, and it sounded great, but I wasn’t sure if it was just the vintage mics or the room itself.

The real eye-opener came when I was working on “The White Masai” at Teldex Studio Berlin. The house engineer, Tobias Lehmann, suggested I try a U47 for vocal recording. I was skeptical, but when I compared it to my modern tube microphone, the difference was like night and day. It wasn’t just a small difference; it was as if we had a completely different singer.

After that experience, I immediately bought my first U47, and since then, I’ve invested heavily in vintage microphones. Now, I have what’s probably the largest collection in the country, possibly one of the largest collections globally.

Eric Valentine, the American engineer, once told me that if I brought my collection to the United States, it would be the third biggest collection of vintage microphones there. He mentioned that even major studios like Avatar or Capitol wouldn’t have more vintage microphones than what I’ve collected.

That said, I still use modern microphones for certain applications. For instance, I prefer my modern mic for recording piano because I don’t want as much harmonic distortion there. But for vocals, the vintage mics provide that nice harmonic sound that’s hard to beat.

Daniel’s iconic CADAC console, used to record Bohemian Rhapsody in 1974. The desk is positioned separately in the room from the Critical Listening Station.

AR: Before we delve deeper into mixing, I’d like to address an important aspect of recording jazz and acoustic ensembles: microphone bleed or spill. When recording a live jazz band or acoustic ensemble, the goal is often to capture the authentic performance in the room, rather than using overdubs as in pop music. This inevitably leads to some level of spill or bleed between tracks unless each musician is isolated in a separate booth. Many engineers, particularly those from a live sound background, consider this spill problematic. Could you share your perspective on dealing with microphone bleed in jazz recordings? How do you approach this issue, and do you see it as a challenge or potentially beneficial to the overall sound?

DD: Well, if you have a good room and really good microphones, then it’s not so much of a problem. You have to know how to set them up and how to record. One of the reasons why spill can be an issue is, as we spoke about earlier, if you give the musicians headphones. If they play together in one room and you give the drummer headphones, then he can play super loud, which can lead to too much drum on the piano and bass mics.

The challenge is for the drummer to still produce intensity without being too loud. In smaller rooms of about 20 square meters, if a drummer plays fully loud, too many reflections are created, and it’s not going to sound good. A great drummer knows how to play for the room.

A little bit of crosstalk can actually be beneficial. It creates the room sound around everything. We usually use cardioid microphones in jazz to get some directivity. However, with cardioid mics, the sound coming from the back, especially in high frequencies, can be problematic.

Here’s an interesting point: with vintage microphones, the crosstalk sounds a lot better. We’ve tested this with my students. For some reason, when using vintage mics to record all together in one room, we don’t have a problem with bad-sounding crosstalk. But with modern cardioid condensers, we often encounter issues with shabby and cheeky sound from the back.

Too much crosstalk can kill the recording, though. For example, with Pablo Held’s recent recording, we have one track where the drummer played a little louder. It still works balance-wise, but Pablo wants the piano a bit louder. However, if we boost the piano by 3 dB, the crosstalk becomes ugly, affecting the overall room sound. In such cases, we need to find a compromise.

So, in summary, a little spill can be beneficial for creating a natural room sound, but it requires careful management and high-quality equipment to ensure it enhances rather than detracts from the recording.

AR: When it comes to mixing jazz, how do you ensure that all the instruments sound cohesive and part of a unified whole, rather than disconnected individual elements? I’ve noticed that even when there’s a good balance between instruments, they can sometimes sound disjointed in the final mix. What techniques do you use to create a sense of space and integration among the various instruments?

Jorge Rossi auditioning a mix.

DD: This is what truly defines an engineer, and it’s where many fail. It’s not just about getting the balance right; you also need to balance the space. Before you can balance the space, you need to recreate it. No matter how you record jazz, the space is always lost. Even with room mics, you need to recreate it. This is an illusion that good engineers can produce.

The space is virtual because two loudspeakers are not producing any depth by themselves. Your brain is localizing these two loudspeakers and nothing else. If you feel that everything is in a room nicely, maybe the piano in front, drums at the back, or whatever arrangement, this is an illusion we as engineers are creating. This is the most difficult part. I’ll say this drastically: if an engineer can’t do this, they’re not really an engineer. I created a Masterclass for those, that want to learn about that, it’s call the “Reverb Bible”.

AR: That’s interesting. Can you elaborate on how you create this illusion of space?

DD: It’s similar to what happens in cinema. Even in a non-3D movie, you have the illusion of space created by the director, cameraman, lighting, and so on. In music, it’s even more challenging when musicians are recorded separately, which often happens in studios with multiple small rooms.

To create this illusion, you need a really good mix engineer that can take those isolated tracks, recorded in separate rooms, and create the miracle and illusion of a real, believable space with a concept. For this, you also need great monitors. It’s not going to work without them. The key is to create a cohesive sound where all instruments are properly placed in the mix. If you hear a production where, for example, the piano is further away than the drums, or the cymbals are positioned okay but the tom-tom sounds like it’s right in front of your nose, that’s a mistake. The drum kit should be in one place, with each part of the kit properly positioned. These aren’t matters of taste; they’re fundamental to creating a believable, cohesive mix.

Pianist Michael Beck in the studio.

AR: You mentioned the importance of equipment. How does this factor into the current state of music production?

DD: This is a significant issue in the current music industry. In many places, even for expensive jazz or pop music, mixing engineers are paid very little, often around 500 euros a day, including the studio. With this budget, it’s impossible to have great acoustics in the control room or a great pair of speakers.

This problem started about 10 years ago when prices went down. Engineers didn’t have a lobby or organize themselves, and now they’re at such a low price level that they can’t possibly produce at a professional level. This, I think, is the worst part of our time regarding music quality – music is often not mixed in real mixing studios, not recorded in real recording studios, and often not mixed by real engineers.

AR: When it comes to the mixing process specifically, what’s your opinion on the difference between analog gear and digital plug-ins? For instance, do you believe there’s a significant difference between using a plug-in recreation of a Fairchild compressor versus using the actual hardware Fairchild in a mix?

DD: It is a significant difference, but it depends on how well things are recorded. Quality must come from somewhere. If you work digitally, you need great converters. If I go out to an analog system, I would say 90% of the time it’s better. But then again at some point you have to go back to the digital domain and AD conversion is not free. It’s got a lot better these days. I invested in MTRX converters, which are probably the best multi-channel converters you can get. They’re made by Digital Audio Denmark. there really great. To record my Mix-Bus back to the Computer I invested in an expensive AD Converter by Weiss Engineering. I also monitor through a DA Converter that was al;so made by Weiss Engineering.

AR: What’s your approach to mastering?

DD: Nowadays, I just see myself as a sound specialist and I want to deliver a great sounding master mix, usually at 96kHz. I just send that to the client. If they want to make a DDP file with it, they can do it. If they want to have 48kHz or 44.1kHz, they can do it with somebody else, but I create one finished file that sounds great.

AR: Earlier we discussed recreating room sound. Now, I’d like to get your opinion on the current trend towards immersive sound. Platforms like Apple Music and Tidal are offering binaural audio, Dolby is heavily investing in Atmos, and there’s also the Auro 3D format. What are your thoughts on immersive sound technologies and their impact on music production and listening experiences?

DD: It’s great for cinema. I actually do some Atmos mixes and specialized in 3D about 25 years ago, long before Dolby Atmos existed. We did music sound designs for museums where we had our own 3D system.

In short, it’s great if the music is also played back in 3D. However, it’s problematic if the music is not played back in 3D, because most artists aren’t going to make a separate stereo mix. But stereo is what we listen to most often.

AR: Can you elaborate on the challenges of 3D audio for home listening?

DD: The main issue is unpredictability. Most people don’t have a proper 3D speaker setup at home. They might have a soundbar trying to create a 3D illusion, but the results vary greatly depending on the room and the type of equipment and decoders. Moreover, all the decoders for headphones sound totally different. So if you listen to a 3D mix on speakers and then on headphones, depending on whether you’re using Apple or Tidal, you’ll get three totally different sounds. There’s just no control over how it ultimately sounds to the listener.

AR: What do you think is a better approach?

DD: I believe it’s better to create both an immersive mix and a stereo mix. Peter Gabriel did this on his latest album. He even created two different stereo mixes, which I think is a great idea in this streaming era. People can choose between mixes by different engineers, presenting the music in different ways. Then there was a third mixer who created the 3D mixes. This might be the way to go.

AR: What about binaural audio for headphones?

DD: Personally, I don’t like to listen to mixes for binaural. At first, you think it sounds big, but then it feels unnatural and full of effects. Because you never hear a perfect mix anymore, it’s not good for your ears. Maybe we should have just one standardized algorithm that creates the binauralization across all platforms like YouTube, Apple, and Tidal. Then mix engineers could adapt for binaural listening.

AR: So, in your opinion, is the trend towards immersive audio beneficial?

DD: In the end, if you do the 3D thing right, it’s even more expensive in production. And I guarantee you, if you give the listener a good stereo production, they will be as happy as if they listened to a 3D production at home. Stereo is great, and a perfect mix by a skilled mixing engineer can present the music exactly as intended. This is not always achievable in 3D.

AR: I wanted to move on to the subject of education. I know this is something you’re involved in, teaching at Basel and Zurich. Could you talk about your vision of education in sound engineering? How has it changed since the 70s and 80s when most learning happened on the job?

DD: Education in sound engineering is a complex topic. In the 70s, especially in America, you’d typically start in a studio, hopefully with a mentor, and then prove yourself through hard work and learning the systems. Nowadays, with formal education options available, it’s a different landscape, which has both advantages and risks.

In Europe, there’s a tendency to approach sound engineering very academically, trying to calculate and measure everything. While this scientific approach has its merits, it doesn’t necessarily produce great mixers. We risk creating technicians who understand the theory but may lack practical skills.

Daniel’s extensive selection of analog outboard gear is exceptional, analog processing is an essential element in his mixes.

AR: How do you think this academic approach compares to the more hands-on learning of the past?

DD: I believe we should consider going back to some aspects of the old system. In Switzerland, we have the “Lehre” system, which is like an apprenticeship. For many professions, instead of studying at a university, you learn directly from a company doing the work. I think for sound engineers who want to be good sound-wise, it would be important, to not only study at the universities, but maybe also consider spending a lot of time in studios, as an intern.

AR: Can you give an example of how this practical approach differs from the academic one?

DD: Certainly. I remember recording a classical violin where I intuitively knew where to place the microphone. An assistant, who was studying to be a Tonmeister, thought the placement was incorrect based on what he’d learned in theory. But when he listened, he admitted it sounded great. The theory taught him one thing, but practical experience and intuition led to a better result.

AR: How do you approach teaching given these differences between theory and practice?

DD: In my teaching, I try to focus on teaching students how to listen. That’s the most crucial skill. You need some technical knowledge, of course, but it’s more important to develop practical skills and intuition. It’s similar to how learning to play an instrument is separate from studying music science. They’re related but distinct skills.

The most important thing is having lessons with a real mentor who has practical experience. In music education, this is well understood – you learn to play an instrument from a musician, not a theorist. Sound engineering should be approached similarly. We need to balance the scientific understanding with practical, hands-on experience and mentorship.

AR: Can you tell us about your current studio setup and how you approach recording and mixing projects now?

DD: Certainly. I’ve completely shifted my focus towards mixing, moving away from recording in my own space. My new studio in Himmelried is purpose-built for mixing, featuring a monitor setup on one side and an analog mixing setup on the other. It’s an 80 square meter space designed to be technically perfect, with top-of-the-line acoustics and equipment that potentially surpasses even major facilities like Abbey Road or big American studios.

While I no longer record in my own studio, I have several options for recording projects. My previous studio in Basel has been converted into a dedicated recording room, including a 35 square meter isolation booth. For larger room sounds, sometimes we can record at the Jazz-Campus Basel, however then, the project must have an educational value. For even more spacious recordings, we sometimes go to Bauer Studios. We also have access to a room owned by composer Nicky Reiser, for larger projects.

When it comes to recording in smaller spaces, I believe the key is to have control room-like acoustics to minimize bleed and excessive reflections. Absorption is crucial in these environments. If I have to record in small rooms, then the drier the better. I’ll then recreate the space later in the mix.

This setup gives me the flexibility to handle different project needs while allowing me to focus on mixing in my purpose-built studio. It ensures that I can deliver the highest quality mixes while still having access to excellent recording facilities when needed. It’s really about having the best of both worlds – a dedicated mixing environment and access to various recording spaces to suit any project.

AR: Your new studio setup seems quite unique. Can you tell us about the layout and why you designed it this way?

DD: Absolutely. The studio has two distinct ends – one for analog and one for digital mixing. As far as I know, nobody has done this before, but I believe it’s the right approach.

AR: That’s interesting. Can you tell us about some of the key equipment in your studio?

DD: Sure. One of my prized pieces is the Unfairchild compressor from Undertone Audio. It’s a recreation of the Fairchild, which is great because the original Fairchilds are extremely expensive and require frequent tube replacements. I also have a Fairman Tubemaster EQ, probably the best tube EQ you can get. Almost every production goes through this EQ – it doesn’t do a lot, but what it does is really magical. There are also some 1176s and a Klangfilm microphone preamplifier that I use to amplify a reverb plate. There is a great deal more but way to much to mention here.

AR: The acoustic treatment in your studio sounds quite advanced. Can you elaborate on that?

DD: Yes, we’ve done some special things with acoustics. We actually absorb bass through the floor. Under the floor, it goes one meter deeper, and behind the monitors, the floor is open. It’s all calculated so that the bass energy goes into the floor and is absorbed there. The speakers also stand on one-meter-high concrete stands that aren’t connected to the rest of the floor. This prevents the speakers from exciting the floor, which is common in many studios. We wanted it to be perfect.

AR: You mentioned Strauss mastering speakers. What makes these so special?

DD: These speakers were custom developed for Sony’s music studio in Tokyo. Sony wanted the most accurate monitors possible and held a contest for speaker designers. Strauss, a Swiss electroacoustic expert, won with his concept. The drivers in these speakers barely move, which eliminates intermodulation distortion. They can reach down to 30 Hz without heavy use of bass reflex. Sony engineers said they’d never heard such accurate mastering monitors before.

AR: These speakers sound quite expensive. How do you justify such an investment?

DD: They are indeed expensive – around $100,000 for a pair. But for a professional at the top of their game, it’s a worthwhile investment. When I was young, I couldn’t really afford them, but I bought them anyway because I knew I needed them to compete at the highest level. It’s about having the best tools for the job. Even established mixers like Eric Valentine have invested in these speakers after hearing them. In this industry, if you want to be the best, you need to have the best.

AR: Thanks Daniel, that’s a great way to wind up this interview. Thanks so much for taking the time, I really appreciate it and I know our readers will find it highly interesting.

DD: Thanks Andrew, you’re welcome

It’s clear that Daniel brings a wealth of experience, technical knowledge, and artistic sensibility to the field of audio engineering, particularly when it comes to recording jazz. His journey from a teenage enthusiast to a renowned professional showcases the importance of both practical experience and continuous learning in this field. Throughout the interview, Dettwiler emphasizes the importance of understanding the artistic vision of a project, adapting to different recording environments, and maintaining a focus on the end goal of creating exceptional recordings. His approach to audio engineering, blending technical expertise with musical sensitivity, serves as an inspiring model for those looking to excel in this challenging and rewarding field.

![]()

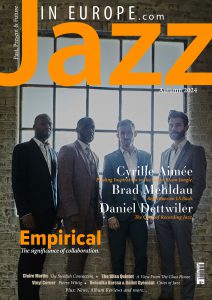

This interview was condensed and featured in the Autumn 2024 edition of the Jazz In Europe Magazine. This edition features in-depth interviews with notable artists such as UK band Empirical and Brad Mehldau and articles exploring the jazz scenes in Budapest and Sweden through conversations with artists like Veronika Harcsa, Bálint Gyémánt, and Claire Martin.

This interview was condensed and featured in the Autumn 2024 edition of the Jazz In Europe Magazine. This edition features in-depth interviews with notable artists such as UK band Empirical and Brad Mehldau and articles exploring the jazz scenes in Budapest and Sweden through conversations with artists like Veronika Harcsa, Bálint Gyémánt, and Claire Martin.

The magazine also includes a special “Vinyl Corner” segment featuring Pierre Wittig, an audio technician specializing in high-quality amplifier restoration. Additionally, readers can enjoy album reviews, a thoughtful editorial on jazz’s response to corporate consolidation in the music industry, and a feature on Cyrille Aimée and finding musical inspiration in Costa Rica.

Last modified: November 12, 2024