In speaking to Daniel Dettwiler, one of Europe’s leading recording engineers specializing in jazz, I knew I was in for an enlightening conversation. What was initially planned as a one-hour interview evolved into a comprehensive discussion spanning several hours over two days. Dettwiler’s expertise and passion for his craft were evident from the start, and I found myself captivated by his insights into the world of audio engineering, particularly in the context of jazz recording.

Born in 1974, Daniel Dettwiler has established himself as a renowned Swiss recording engineer and producer. After studying Audio-Design at the Academy of Music in Basel from 1996 to 2001, he founded Idee und Klang Studio in 2002, which has since become one of Switzerland’s premier recording facilities. His impressive portfolio includes collaborations with acclaimed jazz artists and labels, including productions for ECM Records, featuring artists like Pierre Favre. Dettwiler’s client list boasts notable names such as Kurt Rosenwinkel, Nils Wogram, Mark Turner, and Jorge Rossy. In addition to his work as an engineer and producer, Daniel is also a professor at the Jazzcampus Basel and the Zurich University of Arts.

What sets Dettwiler apart in the jazz recording world is his use of an extensive collection of historic microphones, considered one of the most significant in Europe. This, combined with his studio’s impressive analogue outboard gear, allows him to capture the nuances and warmth essential to producing the highest quality recordings.

Delving into the interview, I was eager to explore Dettwiler’s approach to creating the ideal recording environment for musicians. He emphasized the importance of atmosphere, explaining, “For musicians, entering a studio can be an extremely challenging process. They’re aware that time is limited, especially in jazz where budgets are often tight. They might have only one day, or if they’re lucky, two or three days.”

Dettwiler went on to describe the artificial environment of a studio, which can be quite different from the stage musicians are used to. “They might have to deal with unfamiliar equipment, technical problems, or practices they’re not comfortable with. All of this can create stress,” he explained. His goal, he told me, is to create an extremely relaxing atmosphere so musicians can focus on their art.

I was impressed by Dettwiler’s commitment to problem-solving and maintaining a positive environment. “If they’re not happy with something, I try to solve the problem quickly to show that I respect their concerns,” he said. “It’s crucial to avoid getting into negative arguments, even if what they’re saying might not be entirely correct.”

His strategies for maintaining a positive atmosphere ranged from making a well-timed joke to offering supportive words, or sometimes simply listening to concerns and addressing them later. “Sometimes, the best approach is to listen to their concerns, then solve the problem later when you can. Or maybe you create an extra great rough mix for them to boost their confidence,” Dettwiler explained.

I couldn’t help but agree with Dettwiler’s emphasis on creating a comfortable and positive atmosphere, especially when it comes to recording jazz. Given the improvisational nature of the genre, I noted that this approach seemed crucial for capturing the best possible performance on the spot.

Dettwiler enthusiastically concurred, adding, “Exactly, even more important is a great rough mix, because that’s what the musicians are hearing, whether they’re using headphones or not.” He went on to stress the importance of investing in high-quality equipment, even when budgets are tight. “When I was young, I couldn’t really afford them, but I bought them anyway because I knew I needed them to compete at the highest level. It’s about having the best tools for the job.”

As our conversation progressed, we delved into the topic of choosing the right recording space. Dettwiler emphasized that the choice of recording space depends entirely on the concept of the project. “If you want an old school sound or nice room acoustics, you can’t go to a modern studio with four separated rooms,” he explained. “But if you want close recordings with artistry done later in the mix, that kind of studio could work.”

Dettwiler then shared some of the challenges faced in Switzerland when it comes to finding suitable large rooms for jazz recordings. “Many great radio studios have been repurposed or closed,” he lamented. “We once had access to world-class recording rooms comparable to Abbey Road, but they’ve been given to music schools.”

Despite these challenges, Dettwiler insisted that the concept should always come before the budget. He recounted an experience with artist Yumi Ito: “When I was approached to record Yumi Ito’s next album, the manager initially asked about pricing for three days of studio time. I suggested we first meet with Yumi to discuss the concept, recording location, and overall vision. Only after establishing these creative aspects can we determine an appropriate budget and seek funding if necessary.”

Our conversation then turned to the topic of whether bands should play together during recording or not. Dettwiler explained that this decision entirely depends on the project. “But what’s even more important is the overall atmosphere,” he added. “As a sound engineer, I try to ensure that there’s a constructive and pleasant atmosphere between the musicians, and also between the musicians and staff.”

When I asked about his preference for recording with or without headphones, Dettwiler’s response highlighted his flexibility: “It really depends on the project and the musicians’ preferences. The key is to be flexible and find what works best for each specific situation.” He did, however, express a preference for recording without headphones when possible, especially for ensemble sounds.

As we moved on to discuss mixing techniques, Dettwiler shared his insights on what makes a good mix. “There are clear rules for what makes a good mix,” he stated. “If you look at the American jazz scene, whether you prefer the Jim Anderson sound or the Al Schmitt sound, it might be a matter of taste, but both are incredible mixers. They achieve depth, spectral balance of all the instruments, and physical integrity of the instruments. These are key elements of a good mix.”

Dettwiler then compared the American and European approaches to ensuring quality in jazz recordings. “In the United States, established artists would usually not accept a poor mix. Often, they have producers who ensure quality by saying, ‘Hey, you have a great recording, we’re going to a good mixer.’ But in Europe, we don’t usually have this system, except perhaps with labels like ECM.”

He expressed concern about the European system where musicians are often in charge of everything, including the mix. “Musicians are great at composition and leading their bands, but when it comes to translating that sound to speakers, it’s a totally different story than a live concert. They’re not always the best judge of how their music should be mixed and presented in a recording.”

Our discussion then shifted to the topic of immersive audio and 3D mixing. Dettwiler shared his reservations about the current state of 3D audio technology. “If you listen to a 3D mix on speakers and then on headphones, depending on whether you’re using Apple or Tidal, you’ll get three totally different sounds. There’s just no control over how it ultimately sounds to the listener.”

When I asked about a better approach, Dettwiler suggested creating both an immersive mix and a stereo mix. He cited Peter Gabriel’s latest album as an example: “He even created two different stereo mixes, which I think is a great idea in this streaming era. People can choose between mixes by different engineers, presenting the music in different ways. Then there was a third mixer who created the 3D mixes. This might be the way to go.”

I was curious about Dettwiler’s thoughts on binaural audio for headphones. His response was candid: “Personally, I don’t like to listen to mixes for binaural. At first, you think it sounds big, but then it feels unnatural and full of effects. Because you never hear a perfect mix anymore, it’s not good for your ears.”

Dettwiler proposed a potential solution to the binaural issue: “Maybe we should have just one standardized algorithm that creates the binauralization across all platforms like YouTube, Apple, and Tidal. Then mix engineers could adapt for binaural listening.”

When I asked if he thought the trend towards immersive audio was beneficial, Dettwiler was skeptical. “In the end, if you do the 3D thing right, it’s even more expensive in production. And I guarantee you, if you give the listener a good stereo production, they will be as happy as if they listened to a 3D production at home. Stereo is great, and a perfect mix by a skilled mixing engineer can present the music exactly as intended. This is not always achievable in 3D.”

Our conversation then turned to the subject of education in sound engineering, an area where Dettwiler is actively involved, teaching at Basel and Zurich. I was curious about his vision for education in this field and how it has changed since the 70s and 80s when most learning happened on the job.

Dettwiler acknowledged the complexity of the topic. “In the 70s, especially in America, you’d typically start in a studio, hopefully with a mentor,” he explained. He drew a parallel with learning to play an instrument: “This is well understood – you learn to play an instrument from a musician, not a theorist. Sound engineering should be approached similarly. We need to balance the scientific understanding with practical, hands-on experience and mentorship.”

He went on to discuss the current landscape of sound engineering education in Europe. “Nowadays, with formal education options available, it’s a different landscape, which has both advantages and risks. In Europe, there’s a tendency to approach sound engineering very academically, trying to calculate and measure everything. While this scientific approach has its merits, it doesn’t necessarily produce great mixers. We risk creating technicians who understand the theory but may lack practical skills.”

When I asked how this academic approach compares to the more hands-on learning of the past, Dettwiler suggested a potential solution. “I believe we should consider going back to some aspects of the old system. In Switzerland, we have the ‘Lehre’ system, which is like an apprenticeship. For many professions, instead of studying at a university, you learn directly from a company doing the work. I think for sound engineers who want to be good sound-wise, it would be important to not only study at the universities but maybe also consider spending a lot of time in studios as an intern.”

To illustrate the difference between theoretical knowledge and practical experience, Dettwiler shared an anecdote: “I remember recording a classical violin where I intuitively knew where to place the microphone. An assistant, who was studying to be a Tonmeister, thought the placement was incorrect based on what he’d learned in theory. But when he listened, he admitted it sounded great. The theory taught him one thing, but practical experience and intuition led to a better result.”

I was curious about how Dettwiler approaches teaching given these differences between theory and practice. His response emphasized the importance of developing listening skills: “In my teaching, I try to focus on teaching students how to listen. That’s the most crucial skill. You need some technical knowledge, of course, but it’s more important to develop practical skills and intuition. It’s similar to how learning to play an instrument is separate from studying music science. They’re related but distinct skills.”

As our conversation neared its end, I asked Dettwiler about his current studio setup and how he approaches recording and mixing projects now. His response revealed a significant shift in his focus: “I’ve completely shifted my focus towards mixing, moving away from recording in my own space. My new studio in Himmelried is purpose-built for mixing, featuring a monitor setup on one side and an analog mixing setup on the other.”

Dettwiler’s description of his new studio was impressive. “It’s an 80 square meter space designed to be technically perfect, with top-of-the-line acoustics and equipment that potentially surpasses even major facilities like Abbey Road or big American studios,” he explained.

Despite no longer recording in his own studio, Dettwiler has maintained flexibility in his approach to recording projects. “My previous studio in Basel has been converted into a dedicated recording room, including a 35 square meter isolation booth. For larger room sounds, sometimes we can record at the Jazz-Campus Basel, however then, the project must have an educational value. For even more spacious recordings, we sometimes go to Bauer Studios. We also have access to a room owned by composer Nicky Reiser, for larger projects.”

When it comes to recording in smaller spaces, Dettwiler shared his philosophy: “I believe the key is to have control room-like acoustics to minimize bleed and excessive reflections. Absorption is crucial in these environments. If I have to record in small rooms, then the drier the better. I’ll then recreate the space later in the mix.”

Intrigued by the unique layout of his new studio, I asked Dettwiler to elaborate on its design. He explained that the studio has two distinct ends – one for analog and one for digital mixing. “As far as I know, nobody has done this before, but I believe it’s the right approach,” he said.

Dettwiler then shared some details about the key equipment in his studio. “One of my prized pieces is the Unfairchild compressor from Undertone Audio. It’s a recreation of the Fairchild, which is great because the original Fairchilds are extremely expensive and require frequent tube replacements,” he explained. “I also have a Fairman Tubemaster EQ, probably the best tube EQ you can get. Almost every production goes through this EQ – it doesn’t do a lot, but what it does is really magical.”

The acoustic treatment in Dettwiler’s studio is particularly advanced. “We’ve done some special things with acoustics,” he told me. “We actually absorb bass through the floor. Under the floor, it goes one meter deeper, and behind the monitors, the floor is open.”

As our interview drew to a close, I found myself in awe of Dettwiler’s depth of knowledge and his innovative approach to recording and mixing. His journey from a teenage enthusiast to a renowned professional showcases the importance of both practical experience and continuous learning in this field. Throughout our conversation, Dettwiler consistently emphasized the importance of understanding the artistic vision of a project, adapting to different recording environments, and maintaining a focus on the end goal of creating exceptional recordings.

Dettwiler’s approach to audio engineering, blending technical expertise with musical sensitivity, serves as an inspiring model for those looking to excel in this challenging and rewarding field. His insights into creating the right atmosphere for musicians, choosing the appropriate recording space, and navigating the complexities of modern audio technologies provide valuable lessons for both aspiring and established sound engineers.

Reflecting on our conversation, it was clear that Daniel Dettwiler brings a wealth of experience, technical knowledge, and artistic sensibility to the field of audio engineering, particularly when it comes to recording jazz. His dedication to his craft, combined with his willingness to adapt and innovate, continues to shape the art of jazz recording in the modern era.

![]()

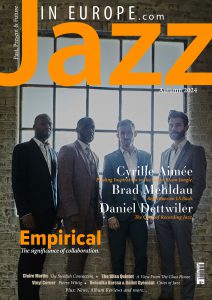

This article is featured in the Autumn 2024 edition of the Jazz In Europe Magazine. This edition features in-depth interviews with notable artists such as UK band Empirical and Brad Mehldau. Readers will find insightful pieces on the craft of recording jazz with Daniel Dettwiler, and explorations of the jazz scenes in Budapest and Sweden through conversations with artists like Veronika Harcsa, Bálint Gyémánt, and Claire Martin.

This article is featured in the Autumn 2024 edition of the Jazz In Europe Magazine. This edition features in-depth interviews with notable artists such as UK band Empirical and Brad Mehldau. Readers will find insightful pieces on the craft of recording jazz with Daniel Dettwiler, and explorations of the jazz scenes in Budapest and Sweden through conversations with artists like Veronika Harcsa, Bálint Gyémánt, and Claire Martin.

The magazine also includes a special “Vinyl Corner” segment featuring Pierre Wittig, an audio technician specializing in high-quality amplifier restoration. Additionally, readers can enjoy album reviews, a thoughtful editorial on jazz’s response to corporate consolidation in the music industry, and a feature on Cyrille Aimée and finding musical inspiration in Costa Rica.

Last modified: November 10, 2024