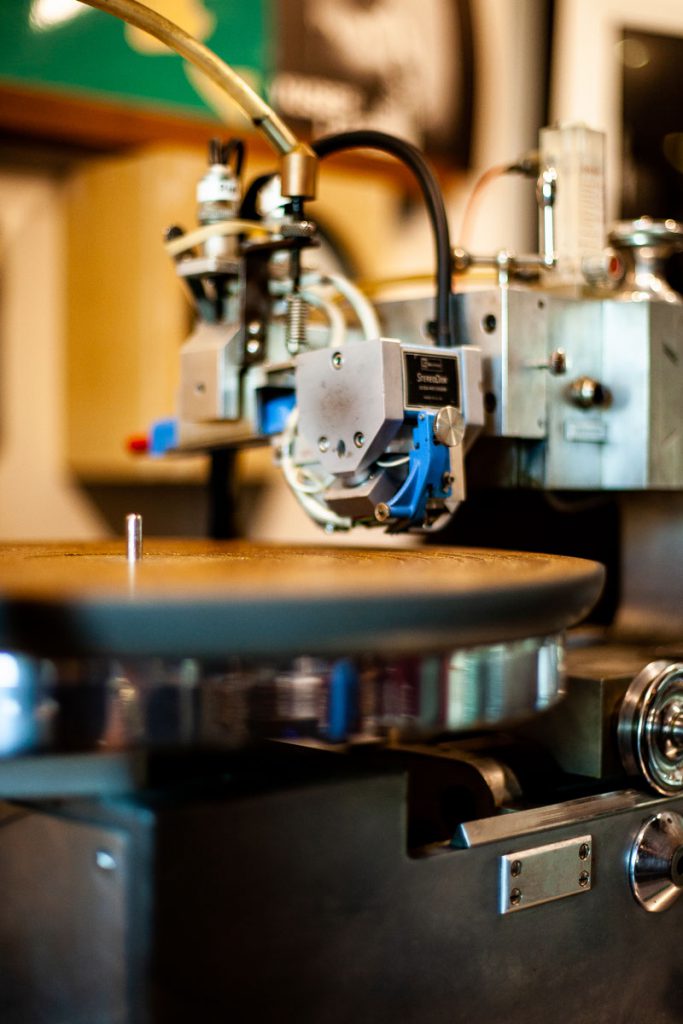

Blue skies and a gentle warm sun adorn my walk to the offices and studios of Gearbox Records, just a 20 minutes walk from King’s Cross Station. The London label’s location has not changed for years and, being back there since the first time I visited in 2015, made it an even more interesting trip. I enter the main room, a kind of lounge-studio paradise for vinyl junkies, a lot of precious and beautiful gadgets as well as vinyls are on show, this awakens thieving instincts in me. But more of this later…

I am meeting: firstly, Darrel Sheinman, founder and, quoting from one of my old scripts, “the engine behind Gearbox Records’ machine”, then Caspar Sutton-Jones, mastering engineer and Justin James, the label’s commercial director.

On this visit, my aim is to talk more in depth about the vinyl side of things and how Gearbox has become such a great label not just in London, but worldwide.

I sit down with Darrel in their magnificent lounge-computer-museum room and I confess to him that I feel like stealing all the machines and vinyls in sight in the room. He laughs a warm and perhaps rather incredulous laughter, understandingly grasping my thieving instinct and abstaining from calling the Police instead.

I sit down with Darrel in their magnificent lounge-computer-museum room and I confess to him that I feel like stealing all the machines and vinyls in sight in the room. He laughs a warm and perhaps rather incredulous laughter, understandingly grasping my thieving instinct and abstaining from calling the Police instead.

We start by remembering that Gearbox has now been in operation since 2009 and so this year represents an important milestone for the label: 10 years.

So how did it all start for him then? How has the label grown to date? He explains that in 2009, Gearbox was a hobby label. He was at another industry and had also been a drummer for a while, he then decided to take a big interest in audio files and equipment, mastering and cutting records. So whilst in the process of restoring, he learnt how to cut records, too. He also decided to run Gearbox as a commercial studio. From 2009 to 2013, for example, after the studio was built in 2012, it was mainly a hobby and they were essentially licensing about 500 records from all the rights to the records from the BBC and things that had never been released before. They would just do a limited run of about 500, this, in turn, would sell out. So, they developed more and did more releases. By that time Darrel was full time together with Adam Sieff, his then business partner. Adam has now retired but is still a small shareholder. Gearbox were basically doing more frontline, contemporary material as well, principally jazz, but also folk and electronic music, although being much more picky in those genres.

Darrel explains then they “sort of stumbled across the new jazz scene, almost like a jazz journey. And that’s why we’ve suddenly found that we are signing all these artists like Theon Cross, Binker & Moses. It’s been good for us. We just happened to have luck, it’s not skill. And I’ve always taken the view – Darrel continues interestingly- that if I sign what I like, then someone else likes it too. The money spent on marketing to get that word out has probably been the best deal, it’s not linear, but there’s a relationship somewhere there”.

As previously mentioned, I last visited Gearbox in 2015, so this time I want to give the readers of Jazz in Europe a clear sense of what Gearbox has achieved specifically in the growth in vinyl production. Firstly, Darrel explains that they do do digital, in fact they do all formats now, and that’s worth noting. In fact digital is probably the fastest growing parts of their stable at the moment. He continues saying: “What’s interesting about digital is that it is a great marketing tool to sell vinyl. What’s changed in the market is that when I started back in 2009, vinyl was really something no one thought was coming back. It was very much a specialist product for high-end and audio file and specific collectors. It continued on that vein for a while and then vinyl started coming back and so the ability to make better productions became more important. We got known for putting out really good productions and therefore we attracted the customers that way as well as the content that, hopefully, was good too. Following on from that everyone was putting download cards in their vinyls and trying to sell them that way. You know, there were all sorts of gimmicks and marketing tricks, free downloads, etc, to basically get people to buy vinyl. Now that’s just not relevant because vinyl has got its own life. It’s definitely back. And, as you know, it doesn’t need any tricks and gimmicks, you’re taking away from the artist when you get free downloads. So we stopped doing it, we were one of the first to stop doing it in fact, and now we just sell all the format separately”.

More specifically and thoroughly interesting, Darrel explains that “what we’re finding is that the streaming growth is providing a platform for us to tell people about the content we’re putting out. And what happens is after they’ve done their rental or streaming and they really like it, they then decide to buy the Bible, hopefully. So I think that’s how the market has changed what we do and we’ve adapted to the market and, principally it’s this change of sales mix and how it’s affecting vinyl sales is very important. What we’ve also noticed is because there’s a bigger market in vinyl, it’s less of an audio file specialist product. So it’s no longer important to be at 180g. It’s not so important to do this, especially with this new jazz scene which is attracting a younger hip hop, grime audience, a crossover audience. Sometimes you have to actually make it cheaper, right? So you might end up being, you know, at 140g which is suddenly acceptable especially when making double albums. So these subtle changes have happened, yes, but we’re selling more records as a result”.

More specifically and thoroughly interesting, Darrel explains that “what we’re finding is that the streaming growth is providing a platform for us to tell people about the content we’re putting out. And what happens is after they’ve done their rental or streaming and they really like it, they then decide to buy the Bible, hopefully. So I think that’s how the market has changed what we do and we’ve adapted to the market and, principally it’s this change of sales mix and how it’s affecting vinyl sales is very important. What we’ve also noticed is because there’s a bigger market in vinyl, it’s less of an audio file specialist product. So it’s no longer important to be at 180g. It’s not so important to do this, especially with this new jazz scene which is attracting a younger hip hop, grime audience, a crossover audience. Sometimes you have to actually make it cheaper, right? So you might end up being, you know, at 140g which is suddenly acceptable especially when making double albums. So these subtle changes have happened, yes, but we’re selling more records as a result”.

Talking about vinyl also means touching upon that dreaded but necessary beast that is ‘the sales”, the efficiency of sales. So I asked Darrel which, in terms of revenues, had the advantage.

He told me that vinyl has the bigger margins, but “that the problem is also that it is terrible for the cash flow because one has to make the products”. One great example, he continues, is the Monk album (an album of previously unreleased tracks and one that appears on my top 10 for 2018 incidentally). Gearbox made that product in June. It actually took three years to get that cleared with the lawyers! Eventually they got the clearance, made the product in June of 2018, released it in September the same year, but the distribution didn’t pay them. They got their first cheque in January this year. “That run – Darrel points out – was for 10,000 records. For a small company that’s a lot of money to tie up in products. And basically the company does not get any money back until much later. This is why small labels go out of business. It is because of this cash flow history. So digital is really nice because there’s none of those production costs. One uploads the product on Spotify as your distributors, but at least one’s getting paid pretty soon after the release. And that’s very powerful. So in a way it supports the vinyl sales. It’s always been mostly vinyl. I suspect that mix is going to change. I think vinyl would still go up. It’s not going to go down, but digital will start to equal it”…

Editors Note: Here’s an overview of Erminia Yardley and photographer Carl Hyde’s day which they spent at Gearbox Records in London. Reporting on this innovative, vinyl based label. All in all a great read. Published in full in the Spring edition of the Jazz In Europe Magazine. You can either view the magazine online or order your hard copy at the link below.

Last modified: April 26, 2020