Today, May-26, 1926 a music giant was born. Miles Davis, often named „Prince of Darkness“, was an original, lyrical soloist on the trumpet and demanding group leader. He was the most consistently innovative musician in jazz from the late 1940s through the 1960s. Miles Davis was one of the most famous jazz musicians of the 20th century.

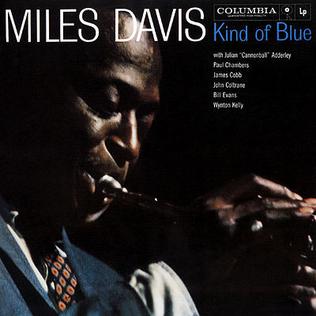

He died on September-28, 1991, at the age of 65. His story is one of ups and downs, of intoxication, fame and restlessness. Davis landed his greatest coup in 1959 when he recorded the album “Kind of Blue”. For this album he only brought his band to the studio with outlines of the compositions for the two recording sessions. It was important to him that the pieces should have a modal character, in this he meant that they should be based on the scales of the church modes and should no longer be functionally harmonious. Miles wanted a sound in which a feeling, a memory should be captured: where, as a boy in Arkansas – his wealthy grandfather who was farm owner, where Davis often spent his holidays – he walked the dark country road and suddenly out of one nearby church hears the singing of a gospel congregation. He wanted to hear the gospel, but also the running noise in the music, and the sound of a kalimba. In the run-up to the recording he had seen the Ballet Africaine from Guinea in New York and was fascinated by the sounds of the thumb piano, the polyrhythmics and the pull of African music.

He died on September-28, 1991, at the age of 65. His story is one of ups and downs, of intoxication, fame and restlessness. Davis landed his greatest coup in 1959 when he recorded the album “Kind of Blue”. For this album he only brought his band to the studio with outlines of the compositions for the two recording sessions. It was important to him that the pieces should have a modal character, in this he meant that they should be based on the scales of the church modes and should no longer be functionally harmonious. Miles wanted a sound in which a feeling, a memory should be captured: where, as a boy in Arkansas – his wealthy grandfather who was farm owner, where Davis often spent his holidays – he walked the dark country road and suddenly out of one nearby church hears the singing of a gospel congregation. He wanted to hear the gospel, but also the running noise in the music, and the sound of a kalimba. In the run-up to the recording he had seen the Ballet Africaine from Guinea in New York and was fascinated by the sounds of the thumb piano, the polyrhythmics and the pull of African music.

The trumpeter, who grew up in a well-off home in St. Louis – his father was a doctor, his mother an elegant socialite. He moved to New York in 1944 at the age of 18 to study at the renowned Juilliard School of Music financed by his father. This only kept him in this temple of classical music for a short time. He quickly got bored of playing in the symphony orchestra, where there was too little to do on the trumpet in a classical setting. The classical repertoire didn’t include an African-American, and then, what of a white teacher who told him about the blues in music history lessons. He was in Harlem most of the time anyway, looking for Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker, whom he had met on guest appearances in St. Louis. Miles Davis played every jam session that came up at Minton’s Playhouse in Harlem and the clubs on 52nd Street, and in 1945 was given the opportunity to make his first record. It was released under the title “First Miles”, and the trumpeter said that he just wanted to forget about it as soon as possible because he was so nervous that he couldn’t even play the simplest things.

William P. Gottlieb, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Davis rejected the standards set for jazz trumpeters in the 1940s by Dizzy Gillespie’s bop improvisations, partly because of his limited technique, but principally because his interests lay elsewhere. He created relaxed, tuneful melodies centered in the middle register. Not reluctant to repeat ideas, he drew from such a small collection of melodic formulae that many solos seemed as much composed as improvised. Harmonically he was also a conservative and tended to play in close accord with his accompanists. Beneath this apparent pervasive simplicity lay a subtle sense of rhythmic placement and expressive nuance. These characteristics have remained central to Davis’s playing throughout his career. Their mature expression first came on the nonet sessions (1949-50), which inspired the cool-jazz movement. Davis’s liking for moderation meshed perfectly with his arrangers’ concern for smooth instrumental textures, restrained dynamics and rhythms, and a balance between ensemble and solo passages. In the 1950s, as cool jazz became popular, Davis ignored this style, instead surrounding himself with fiery bop players.

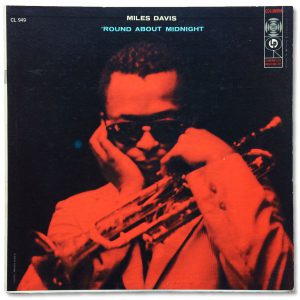

Davis’s fallow period in the early 1950s came to an end with his celebrated blues improvisation Walkin’ in 1954. In a session with Sonny Rollins in the same year he introduced the stemless harmon mute to jazz; its intense sound led to delicate recordings by his first quintet (Bye Bye Blackbird, 1956; ´Round Midnight, September-October 1956), which are even more memorable than the fierce swing of the Garland-Chambers-Jones rhythm section on fast bob tunes. Many jazz trumpeters turned to flugelhorn after Davis had demonstrated its potential in his collaborations with Gil Evans; these recordings offer rare examples in jazz of lush orchestral settings with sustained emotional substance, and present an ideal foil for the relaxed tunefulness, melodic and harmonic simplicity, and subtle swing of Davis’s improvisations. By the late 1950s Davis had tired of bop structures, and turned to a new approach formulated at this time by Gil Evans and Bill Evans and later called “modal playing“. However, the use of modes in Davis’s recordings of 1958 and 1959 (Milestones, So What, Flamenco Scetches) had less significance for the future than the slowing of harmonic rhythm. In place of fast-moving, functional chord progressions, Davis used diatonic ostinatos (vamps), drones, half-tone oscillations familiar from flamenco music, and tonic-dominant alternations in the bass line. Flamenco Scetches is a composition in five segments: the first and third are in static major keys, which some analysts have preferred to call the ionian mode, and the second and the fifth suggest others of the ecclesiastical modes. The fourth section, which gives the piece its name, is based on a flamenco-like scale, manifested most clearly in the oscillation of D and Eb major chords in the piano.

Davis’s fallow period in the early 1950s came to an end with his celebrated blues improvisation Walkin’ in 1954. In a session with Sonny Rollins in the same year he introduced the stemless harmon mute to jazz; its intense sound led to delicate recordings by his first quintet (Bye Bye Blackbird, 1956; ´Round Midnight, September-October 1956), which are even more memorable than the fierce swing of the Garland-Chambers-Jones rhythm section on fast bob tunes. Many jazz trumpeters turned to flugelhorn after Davis had demonstrated its potential in his collaborations with Gil Evans; these recordings offer rare examples in jazz of lush orchestral settings with sustained emotional substance, and present an ideal foil for the relaxed tunefulness, melodic and harmonic simplicity, and subtle swing of Davis’s improvisations. By the late 1950s Davis had tired of bop structures, and turned to a new approach formulated at this time by Gil Evans and Bill Evans and later called “modal playing“. However, the use of modes in Davis’s recordings of 1958 and 1959 (Milestones, So What, Flamenco Scetches) had less significance for the future than the slowing of harmonic rhythm. In place of fast-moving, functional chord progressions, Davis used diatonic ostinatos (vamps), drones, half-tone oscillations familiar from flamenco music, and tonic-dominant alternations in the bass line. Flamenco Scetches is a composition in five segments: the first and third are in static major keys, which some analysts have preferred to call the ionian mode, and the second and the fifth suggest others of the ecclesiastical modes. The fourth section, which gives the piece its name, is based on a flamenco-like scale, manifested most clearly in the oscillation of D and Eb major chords in the piano.

At times, especially during Davis’s efforts to resume his career in the 1980s, the results have been a rough juxtaposition of disparate sounds rather than a fusion, but the album Decoy offers fine examples of his style. Davis himself concentrates on trumpet, but he also plays synthesizer; his performances on both instruments may be heard to advantage on the title track of Star People, an unusual slow blues distinguished by the splashy sound of Foster’s obstinate on a Chinese cymbal. Already the innovator of more distinct styles than any other jazz musician, Davis remains a stimulating leader and masterful soloist until his passing in 1991. Miles Davis’ artistic interest was in the creation and manipulation of ritual space, in which gestures could be endowed with symbolic power sufficient to form a functional communicative, and hence musical, vocabulary. … Miles’ performance tradition emphasized orality and the transmission of information and artistic insight from individual to individual. His position in that tradition, and his personality, talents, and artistic interests, impelled him to pursue a uniquely individual solution to the problems and the experiential possibilities of improvised performance.

In the last year of his life he gave a concert in Berlin and at the same time an exhibition of his drawings and oil paintings was opened in the Amerika-Haus, Berlin. At the time I was producing and hosting a radio jazz show named „Jazzbeats“ and I had the opportunity for an interview with him. He welcomed me in his hotel suite, completely wrapped in silk and relaxed. An easel stood next to him and a picture he was working on was taking shape. An elegant, reclining lady could be seen. While he was having a good breakfast, I asked my questions, which he quietly listened to and finally told me in his rough voice: „Jan, you always have to put yourself ‚In the Now‘, then no questions remain unanswered.“

Featured Header Image by William Ellis

Last modified: June 7, 2023