Best known for her wordless improvisation, English based Jazz vocalist and lyricist Norma Winstone MBE has had a long and successful career, spanning over 50 years. Norma’s many achievements over the years have led to her being highly regarded as one of the most respected jazz singers in the world. Paola Vera met with Norma at her home in Kent, UK to discuss her amazing career.

Paola Vera: You’ve had an incredibly long, successful career, spanning over 50 years and are highly regarded as one of the most respected jazz singers in the world. How did you get into music? What was it like starting out?

Norma Winstone: I always loved it, since I was very small. I always wanted to learn songs, all that I could possibly learn by listening to the radio. During the war, my dad, who was in the army, had heard Sinatra on an on-field radio and had written to my mum saying, “You have got to hear this singer.” I was brought up knowing that he was the best singer of my generation. Another inspiration was Lena Horn in the movie Words and Music with the music of Rogers and Hart (My mum, who loved the cinema, took me to see it). What a vision she was, singing The Lady is a Tramp.

I was about 11 when I began going to Saturday school at Trinity College, learning piano and then organ as a second study. I was always singing and always wanted to sing, but I had no idea how to go about it.

PV: How did you go about it? How did you get into it?

NW: There was a singing teacher in Seven Kings school. I went to him and the first thing he taught me was about breathing, by giving me various breathing exercises. Every week we worked on a song. He played the piano and we’d find the key and I began to build a gig list.

At 17, I discovered jazz. I heard Ella Fitzgerald and Oscar Peterson. I’d be listening to Radio Luxembourg really quietly and every week they’d play this track from Ella and Louis, with The Oscar Peterson Trio and I fell in love with that music. Eventually, I got a record player and my cousin lent me a recording of Ella Fitzgerald singing ‘Air Mail Special’ and ‘Flying Home’ and scat singing and I thought, ’wow this is fantastic’ and of course I imitated it. Another model for me was Carmen McRae, whose version of ‘Star Eyes’ was played a lot on the radio, and I loved the sort of rough sound that she had. Then I heard the Dave Brubeck Quartet playing Jazz Impressions of the USA with Paul Desmond on alto.

At that point, though I hadn’t focused on the fact that they were improvising, it seemed pretty obvious to me that it would be different every time they went around it. It didn’t need explaining that jazz was improving over a sequence.

PV: You have worked with some big names in Jazz. What were those experiences like? Did you ever feel starstruck?

NW: Well, when I was asked to join Vocal Summit, the first gig I ever did with them was in Marseilles and I didn’t know Jay Clayton, Urszula Dudziak or Bobby McFerrin. I was thrown into doing this gig with them, and we had hardly any rehearsals. I did two gigs. Bobby McFerrin was still in the group, (before ‘Don’t Worry Be Happy’, she laughs). I couldn’t believe what he could do. It was very inspiring actually. We went into the dressing room and he was doing Steps ahead and Safari just on his own!

I liked working with Vocal Summit because it was experimental and there was lots of improvisation which I loved, but I knew it was impossible to do what Bobby McFerrin did!

PV: You saw the evolution of jazz in the UK and Europe throughout your career. How have things changed?

NW: Well, I don’t think it’s any easier for people, especially if you’re doing music which is not the mainstream. I’ve always been on the edge, always felt like I was swimming against the tide and somehow couldn’t stop. I met a pianist called Chris Goody and we’d get together and playthings. He knew Margaret Busby who was in a publishing company called Alison and Busby. She also wrote lyrics for tunes like ‘Naima’. I was inspired by her, though I didn’t write words myself at that time, I didn’t think I could.

PV: When did you start writing lyrics and singing them?

NW: When Kenny Wheeler asked me to do some broadcasts with his big band. I met Kenny on the free music scene. The thing is I eventually did find a local trio whose singer was leaving and after I sat in they offered me the gig, so I suddenly had a gig two nights a week. I was working during the day (it wasn’t anywhere near professional) and I used to do all kinds of office work.

Finally, I went along to a gig at the Charlie Chester Club and I sat in with a drummer called John Stevens and he was incredibly enthusiastic and jumped up and said, “I’m going to tell Ronnie Scott about you, he should give you an audition!”. So he got in touch with Gordon Beck and Geoff Klein, who were stars back then. I’d heard them many times on the radio and at Ronnie’s old place in Gerard Street. I was really scared. Anyway, we rehearsed and we kept calling to organise an audition. I didn’t hear anything. Eventually, I went to the club, and after reminding Ronnie that eight months before he promised to invite me for an audition, we got it and he gave me four weeks there opposite Roland Kirk. I think I was on cloud nine. I was nervous and excited all at the same time. This lead to other things for me.

At the same time, I got my first radio broadcast which was an audition. They used to have these half-hour slots around midnight on the BBC. They were recorded in all kinds of places; The Paris Studio, Lower Regent Street; they were all pre-recorded.

My boyfriend at the time heard that Carmen McRae was over from the USA and he found out where she was staying and telephoned her. I would never have done it! He said, “My girlfriend’s a singer. Could she meet you?” He said my name and Carmen replied, “What did you say her name was?” He repeated my name and she said, “Well, I want to meet her because I was lying in bed last night and I put the radio on and she was on.” She heard my first ever broadcast. What are the chances of that? At midnight, for about 15 minutes.

I met her and we did an interview for a Jazz magazine and she was lovely. I remember that she asked me if I played the piano. When I said, “Well, not really. I don’t improvise or know anything about chords.” she replied, “I don’t believe you. I heard the way you were singing.” It wasn’t wordless though. I had another set of words that I was improvising with. At that time I wasn’t doing wordless singing, I was just pulling the melody around, but she could hear that I could hear the changes. So, then John Stevens invited me to join in on some of these free sessions. people like Kenny Wheeler were there. Sometimes Dave Holland came to these sessions. That was before he got the gig with Miles Davis.

Then eventually Kenny started his big band broadcast, and he arranged a standard for me at first. Eventually, he started to write for me as part of the band, and I guess it progressed from there.

Our first trio album titled Azimuth was released in 1977 on ECM, with Kenny Wheeler on trumpet, of course, John Taylor on piano and me on vocals. I also made an album with Jimmy Rowles and one with Fred Hersch.

PV: You are renowned for your lyrics writing. Can you tell us a bit more about your process?

NW: Well, the reason I started to write lyrics was that I wanted to get a different repertoire. There were loads of compositions that I loved, you know, by Ralph Towner and Egberto Gismonti and I thought why not try to write lyrics to them.

So, I wrote words for one of Kenny’s pieces Don No More from the album Windmill Tilter. Then he asked me if I’d write words for the piece Eventually Yours from the album Song for Someone. So, I had a go. But it was most difficult musically because it seemed to be one long sentence. There was nowhere to put a full stop, nowhere to take a breath. So we changed its title to Nothing Changes.

PV: Your career is all the more remarkable because you have managed to balance having a family with creative life. What was it like facing the challenge of juggling motherhood and a singing career?

NW: It was never easy, but you do it somehow and afterwards you look back and think ‘how did I do that?’ Anyhow, John was incredibly helpful. There was no question of “could you look after the kids?” He did that most of the time and if he couldn’t, my mother would help out.

We took the kids with us on a couple of tours and Kenny’s wife Doreen came with us. She was great. She would look after the children when we were doing the gig. They’d come to the soundcheck and they loved it. The first tour they were 4 and 2 then 6 and 4. Then it got difficult with the school. I started to do session work, which stopped me from travelling too much. I was earning good money from the studio work and didn’t have to go away, so that helped.

PV: What do you think about Brexit in terms of its potential impact upon musicians?

NW: I don’t know yet what its impacts will be. But honestly, I can’t see any advantage in it for musicians because they will lose the help the EU gave some of the musical projects. As far as travelling is concerned I don’t know what will happen. I remember that when we were travelling with Azimuth, there were still borders and it was such a drag. We had to get carnets for the instruments for each place. It was a real nightmare, and I certainly hope it’s not going to be repeated. I don’t know what we’re going to gain and, to be honest, I’m not sure anybody does. I don’t think people knew, even the politicians, what they are taking us into or out of. It remains to be seen. Maybe it will be fine. But somehow I doubt it.

PV: What do you think about the evolution of jazz today? Where do you feel the music is headed?

NW: There’s a lot of influences that have come into jazz, such as world music, ethnic stuff. I mean it’s a funny word, jazz. It means different things to different people. Unfortunately, when I look at the programs of some of the festivals that are supposed to be jazz festivals I am not sure whether that’s jazz or not. I suppose if it’s good music, it’s alright, but then people use the word and use the label “jazz” when maybe they shouldn’t. As far as I’m concerned, I don’t worry too much, because I’m still just doing what I do.

I know young singers and musicians who are more likely to worry. The thing is that funding is difficult, much more difficult now than it used to be and may become even more difficult. But if there’s a will there is generally a way! There’s a lot of enthusiasm still from young people; from the ones that come out of the colleges anyway.

I remember somebody asking Stan Tracy once, “There’s been a bit of a resurgence in jazz. Isn’t there a revival?” and he said, “I haven’t noticed anything. It’s always been the same for us.” It’s always been a struggle and I don’t expect that will get any better.

![]()

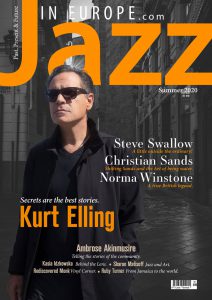

Jazz In Europe Magazine – Summer 2020 Edition

This article is an abridged version of the full interview that appears in the Summer 2020 edition of the Jazz In Europe print magazine.

Also included in this edition are interviews with Norma Winstone Steve Swallow, Ambrose Akinmusire and Ruby Turner. We take a look at some rediscovered Thelonious Monk recordings, Nigel speaks with the painter Sharon Matishoff about her work painting portraits of Jazz Icons and our photo feature for this edition features the work of Polish photographer Kasia Idzkowska.

You can purchase a copy of the magazine here.

Last modified: August 18, 2020