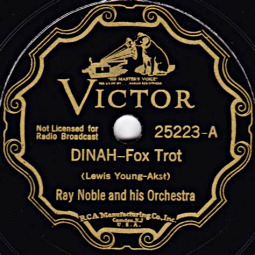

The Dorsey Brothers experience led directly to his being hired by famed British bandleader Ray Noble when the latter came to New York in 1935 and landed a prestigious spot in the Rainbow Room of the newly-built RCA Building. Miller was asked to recruit musicians for his orchestra, no expense to be spared. Glenn responded with some of the finest session men in New York at the time: lead trumpeter Charlie Spivak, jazz trumpeter Sterling  Bose, trombonist Will Bradley, clarinetist Johnny Mince, and legendary Chicago jazz saxist Bud Freeman. Given some freedom by Noble to write however he wished, Miller turned out some outstanding charts, again showing great diversity in approach: Chinatown, My Chinatown; Dinah; and a tongue-in-cheek arrangement of Bugle Call Rag that used quotes from both a sailor song and Ravel’s Bolero. In one of his arrangements for Noble, Way Down Yonder in New Orleans, he first came up with a device that he would re-use several times with his famous civilian band: the riff that starts out softly, almost a whisper, but then gradually increases until he brings it to a roaring climax and then breaks it off to proceed to either the next theme, a variation on the theme, or (as in the case of In the Mood) a diminuendo in the coda. And when Bunny Berigan, Benny Goodman’s star jazz trumpeter, wanted to make his first band records, Miller was the one he turned to. Glenn wrote two brilliant arrangements for Berigan, Solo Hop and In a Little Spanish Town, in one night and recorded them the next day.

Bose, trombonist Will Bradley, clarinetist Johnny Mince, and legendary Chicago jazz saxist Bud Freeman. Given some freedom by Noble to write however he wished, Miller turned out some outstanding charts, again showing great diversity in approach: Chinatown, My Chinatown; Dinah; and a tongue-in-cheek arrangement of Bugle Call Rag that used quotes from both a sailor song and Ravel’s Bolero. In one of his arrangements for Noble, Way Down Yonder in New Orleans, he first came up with a device that he would re-use several times with his famous civilian band: the riff that starts out softly, almost a whisper, but then gradually increases until he brings it to a roaring climax and then breaks it off to proceed to either the next theme, a variation on the theme, or (as in the case of In the Mood) a diminuendo in the coda. And when Bunny Berigan, Benny Goodman’s star jazz trumpeter, wanted to make his first band records, Miller was the one he turned to. Glenn wrote two brilliant arrangements for Berigan, Solo Hop and In a Little Spanish Town, in one night and recorded them the next day.

It was during his stint with the Noble band in 1935-36 that Miller first began toying with the ooh-wah brass (in modest form), wrote a song called Now I Lay Me Down to Weep that was, oddly, never recorded, but which he later turned into his theme song, Moonlight Serenade, and also started to think of a clarinet leading the reeds. The latter was suggested to him by a similar voicing used by the then-famous Isham Jones Orchestra, except that the Jones band used an alto sax lead over tenors and a baritone. But he wouldn’t really start using it until a few months into leading his own first big band in 1937, and then only sporadically.

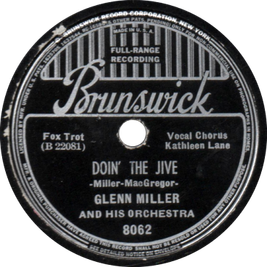

Schuller blasted the dance-crazed public for not recognizing and embracing Miller’s “more advanced approach” over the bland, often stock arrangements played by his former employer Tommy Dorsey in 1935-37, but the problems with the first Miller band ran deeper than that. By his own (later) admission, Miller didn’t really have good enough musicians. When they made their first Decca recording session, he was forced to hire high-priced ringers like famed New Orleans clarinetist Irving Fazola and his former Noble bandmates Charlie Spivak and Sterling Bose to make them sound better, and even then they were only able to record two songs in five hours and neither side was very distinctive-sounding. Yet even by his own account, he kept changing personnel and working on the band, and by later in the year they were turning out some pretty impressive records. Schuller particularly liked his complex arrangement of I Got Rhythm and a Miller original called Community Swing, but there were also some outstanding medium-tempo bouncing vocals by an excellent singer named Kathleen “Kitty” Lane, who unfortunately was not  hired by Miller for his more famous orchestra, and later on there was a very interesting uptempo swing piece that vacillated between minor and major (the middle eight switches to major for the first four bars, then incorporates not one but two key changes in the next two bars with a return to the minor in the final two), included a vocal chorus by Lane, one by the band and a comical spoken exchange between tenor saxist Jerry Jerome and Miller, called Doin’ the Jive. I never could understand why this tune was not revived by the more famous band for Marion Hutton, Tex Beneke and Miller. It was a perfect vehicle…but perhaps he felt the minor-major switches were too complex for his listeners.

hired by Miller for his more famous orchestra, and later on there was a very interesting uptempo swing piece that vacillated between minor and major (the middle eight switches to major for the first four bars, then incorporates not one but two key changes in the next two bars with a return to the minor in the final two), included a vocal chorus by Lane, one by the band and a comical spoken exchange between tenor saxist Jerry Jerome and Miller, called Doin’ the Jive. I never could understand why this tune was not revived by the more famous band for Marion Hutton, Tex Beneke and Miller. It was a perfect vehicle…but perhaps he felt the minor-major switches were too complex for his listeners.

But there was a darker side to this early band: most of the jazz soloists he hired were hardcore alcoholics who either messed up on gigs or missed them entirely. This didn’t sit at all well with the highly disciplined, almost drill-sergeant-like Miller. He gave the band two weeks’ notice on New Year’s Even of 1937. When the band got stuck in a deep winter snowstorm in January 1938 and couldn’t make their next gig, Miller pulled the plug and gave it up. His good friend, jazz critic George T. Simon, got Jerry Jerome a job as jazz tenor saxist with Red Norvo’s band, a move that Miller viewed as a stab in the back, but as Simon put it, “You’re my friend, but so is Jerry. He has a family and needs to eat. I felt it was my duty to help him, and I’d have done the same for you if you were the one in need of help.”

Miller spent two months re-thinking his position and decided to try again, but with a different group of musicians and a different musical mindset. For one thing, his new band was not going to vacillate between two-beat jazz, which he had been raised on (the Dixieland influence) and four-beat jazz, which was clearly more popular. For another, he was not going to mix musical styles but try to create a uniform “sound” that would permeate all of his arrangements whether ballads or jump tunes. And thirdly, although he would audition a large number of musicians and pick the ones who were the best readers and the most technically proficient, he would check out their backgrounds and make sure that none of them were alcoholics or pot smokers. The only holdovers from the earlier band were alto saxist and clarinetist Hal McIntyre, his close friend Chalmers “Chummy” MacGregor on piano and Rolly Bundock on bass. The last-named was kind of a drag since he couldn’t really swing, but Miller kept working with him and finally got him to play with some lift in the rhythm. His first drummer with the new band, who stayed with him several months, was the flat-footed Bob Spangler, replaced in December by the only-slightly-better Cody Sandifer. Interestingly, although he had down-home-folksy tenor saxist and singer Tex Beneke and his most famous balladeer, Ray Eberle, with him from the start, his first “girl singer” was Gail Reese, who was only slightly less good than Kathleen Lane and who sounded nothing like Marion Hutton.

But where did the perennially broke Miller get the funds to re-start his band? Believe it or not, from his old boss Tommy Dorsey. Dorsey, like his former Ben Pollack bandmate Benny Goodman, really did believe in Miller’s talent as an arranger and his discipline as a builder of orchestras to be a success, yet there was more to it than that. Tommy was a bit of a gambler and thought of himself as a hotshot businessman who could outsmart the agents and executives who ran the music business. He was so sure that Miller would be a success this time that he thought Glenn would cut him in on the profits of the band when they hit it big. It came as an unpleasant shock to him when Miller, through his agency at the time (the powerful firm of Rockwell-O’Keefe) mailed Tommy a check paying him back with interest and a personal note from Miller thanking him for his investment.

Miller was extremely lucky to be booked into the Paradise Restaurant in New York starting on June 14, 1938 for two weeks, because this gave him a powerful radio spot on the NBC Blue Network, an exposure he never got with the earlier band (who had just one gig with a very limited radio range). This led to further bookings in and around the New York-New Jersey area and, in September 1938, to his recording contract with RCA’s Bluebird label. Unfortunately, this was one time when Miller somehow made a very poor decision to write and record a two-part arrangement of Thurlow Lieurance’s By the Waters of Minnetonka, surely one of the most vapid charts he ever wrote. It was an absolute bomb, as were several of his first records. The only ones to make a splash were his sensitive arrangement of My Reverie, based on the Debussy piece, with a nice vocal by Eberle, and a fairly good arrangement of King Porter Stomp.

But the band was clearly on the way up. In December, the Paradise Restaurant brought him back, this time for an extended engagement, and in the spring of 1939 he was booked into the even more prestigious Glen Island Casino in New Rochelle, New York for the entire summer. By this time, too, he had replaced Gail Reese with teenaged-sounding Marion Hutton in order to appeal more to Middle America, expanded his brass section from six to eight musicians (four each trumpets and trombones), hired a helpmate in arranger Bill Finegan and finally gotten a superb big-band drummer, Maurice “Moe” Purtill. The latter two also came from Tommy Dorsey, who had tried both of them out but wasn’t crazy about them.

The Finegan-Miller collaboration, like Miller’s other collaborations with such gifted arrangers as Eddie Durham, Jerry Gray, Fred Norman, Billy May, Bill Challis and Mary Lou Williams, all of whom wrote for his orchestra, has always raised questions. Gray, May, Challis and Williams never said a word about how Miller adapted and rearranged their scores because the records were successful and the finished products were superb, but in later years May carped that Miller wouldn’t record half of his charts and Finegan complained that Miller stole ideas from him and didn’t always give him credit, or that he tweaked his arrangements behind his back. Well, I’m not so sure what “behind his back” meant since the band was playing them almost constantly in live performances and broadcasts, but as Bobby Hackett pointed out, Miller was indeed always tweaking arrangements his band played. Undoubtedly the most famous, but not necessarily the most artistic, of these was In the Mood. The little riff tune that we now know by that title first appeared on a Wingy Manone disc in 1930 under the title Tar Paper Stomp. Joe Garland, a black arranger, created a multi-themed version of the piece for Edgar Hayes’ band, which they recorded in February 1938. The record went nowhere, probably because there were too many themes for listeners to follow. Artie Shaw’s wildly popular 1938 swing band included a slowed-down version of In the Mood labelGarland’s arrangement in their broadcasts, but again the piece gained little traction and Victor wouldn’t even allow Shaw to record it. Miller, with some input from both Finegan and Durham, used just two themes, then went into a chase chorus by his two tenor saxists, Beneke and Al Klink. Afterwards he repeated the first theme, then started the slow, gradual decrescendo, extending the length of each chorus an extra two bars with pedal-point trombones, then brought it back forte with the trumpets blasting. It was ingenious; it caught dancers’ attentions; and although it didn’t sell well at first, by 1941 it was the band’s most instantly recognizable jump tune.

What most people don’t know, however (even Schuller was unaware of it when he wrote his book The Swing Era), is that even around the time he recorded this tightened version of In the Mood, Miller was playing the FULL arrangement, much like the Edgar Hayes recording, in his live performances and broadcasts. You can hear a rare example of this on YouTube below and moving the cursor to 35:03.

Thus, this was a rare instance of Miller initially misjudging his own work. It was only after the record began to take off that his performances were tailored to the shorter version of the tune.

Miller also had an obvious effect on Durham’s stupendous arrangement of his own Slip Horn Jive, mostly in the irregular six-bar intro and the reed voicing that enriched the sound as well as on Finegan’s Little Brown Jug. For the latter, he helped devise and orchestrate the slow, gradual opening crescendo from just piano and drums to the full band, including one of his trademark sounds, the rapid ooh-wah sound of plunger brass. It should also be pointed out, though it is often overlooked, that Miller himself was one of his early band’s finest jazz soloists. Although he clearly did not have the smooth, rich tones of Teagarden, Dorsey or Lawrence Brown of the Duke Ellington band, he played interesting improvisations that fit the surrounding material.

Last modified: May 29, 2019